The problem of second language acquisition has been studied by researchers of different countries for many years. Their interest to the problem is not a groundless one. For example, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, the population of non-native speakers of English increased dramatically in the past decade (International Reading Association, 1993). More and more people come to Russia to study or to work and they also need to learn the second language quickly and effectively. To help adult non-native speakers to learn a second language is one of the important missions of adult education. To carry out this mission effectively, we need to have a sound theory to guide us. There are many existing second language acquisition theories (SLA), such as Krashen's Monitor model (1981, 1985, Schumann's Acculturation theory (1986, 1978), and Cummin’s Dual Iceberg models (1986, 1981),

In the last two decades, the bridge between the researchers and practitioners have become even more tenuous. Some of this dissonance is created by the fact that researchers are interested in discovering and examining the principles that will explain Second Language Acquisition (SLA) while practitioners are more concerned with what methods will work in dealing with students who are struggling to acquire a second language (L2). Despite this tension, there have been attempts to provide theoretical constructs to better understand how SLA occurs.

We will now examine five models of L2 acquisition which seek to account for the role of social factors. The five models reflect the primary research interests of their progenitors and the contexts in which they have worked. Two of the models — Schumann's Acculturation Model and Giles and Byrne's Inter-group Model — have been designed to explain L2 learning in natural settings, in particular those where members of an ethnic minority are learning the language of a powerful majority group. The third model — Gardner's Socio-educational Model — was derived mainly from studies of L2 learning in language classrooms, although Gardner argues that it is also applicable to L2 learning in natural settings. Krashen’s Monitor Model and Cummnis’s “Dual iceberg” model are also applicable for natural and educational settings.We will start with the work of Stephen Krashen and his Monitor model. Monitor Model

Stephen Krashen, professor at University of Southern California, distinguishes between learning and acquisition. Acquisition is an unconscious process where no formal classroom instruction is involved. Language is "picked up" in these natural settings; this is similar to how children learn their first language. Learning, however, is about conscious knowledge and the application of rules and structures. This is often what becomes the outcomes of classroom instruction in a second language (Krashen, 1982).

Learning about a language often operates as a monitoring or editing function. However, it is not enough to understand grammatical rules. These techniques may have little to do with real communication, thus explaining the limited success of previous methods for SLA. This "monitor model" notes that acquisition and learning are two separate processes that coexist in the adult and both are utilized in different ways. Therefore, where as a foreign student's stronger language skills (especially in reading, grammar, and writing) is due to what s/he learned in his/her home country, an immigrant student's mastery of aural comprehension is due to the acquisition of language resulting from the necessity of daily survival. To be successful, SLA programs need to focus on both aspects of language acquisition.

Two collieries to the monitor model include the input and affective filter hypothesis. The input hypothesis focuses on student learning and notes that some language acquisition will occur whenever individuals are placed in a foreign language environment (Krashen, 1982). However, successful SLA takes place when the student is provided with some initial clues that facilitates the acquisition process. This is why as tourists in a foreign country we may gain better comprehension if the native speakers addressed us with gestures and simplified speech, thus providing a context for better understanding. The student's native language is therefore critical to helping better understanding and acquiring the English language.

The affective filter hypothesis examines outside factors that may affect SLA. These include various societal and emotional issues. Krashen notes that students can be effected by levels of motivation, self-confidence, and anxiety. While inputs may be the direct avenue to language acquisition, these affective qualities can impede or facilitate the input delivery. Thus, SLA classrooms should not only tailor pedagogical techniques to supplying comprehensible input for all students but also creating an environment that encourages a low affective filter. Part of language acquisition, then, is the formation of safe, caring environments of learning. Dual Iceberg Model

Jim Cummins, of the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, has advocated a developmental interdependency hypothesis. He has proposed the concept of the "dual iceberg," where the skills of different languages reside in the same part of the brain, differing at the surface yet connected at the base. This interdependence hypothesis implies that students without a firm foundation in their native language will find they face difficulty in mastering both languages. However, past research would argue against this sense of urgency for Limited English Proficient (LEP) students to master foreign language. Cummins notes the "virtually every bilingual program evaluated during the past 50 years show either no relationship or a negative relationship between amount of school exposure to the majority language and academic achievement in that language" (Crawford, 1991).

Students must attain cognitive-academic language proficiency (CALP) if they are to achieve in their school subjects. The reality is that most LEP students are not allotted the opportunity to take the five to seven years it normally takes to develop CALP. This is quite different from acquiring basic interpersonal communicative skills (BICS). Like Krashen, Cummins notes that there are really two contrasting language skills that can be developed by LEP students: functional English and academic English. Unfortunately, many educators confuse the development of functional English as an indicator for full English acquisition. This sets up many LEP students for failure in the academic subjects, especially if the development of CALP is disrupted at an early age. Often, what results in poor language skills is both the first and second languages. Acculturation Model

Schumann's Acculturation Model was established to account for the acquisition of an L2 by immigrants in majority language settings. It specifically excludes learners who receive formal instruction. Acculturation, which can be defined generally as 'the process of becoming adapted to a new culture', is seen by Schumann as governing the extent to which learners achieve target-language norms. As Schumann puts it: ... second language acquisition is just one aspect of acculturation and the degree to which a learner acculturates to the target-language group will control the degree to which he acquires the second language.

In fact, Schumann distinguishes two kinds of acculturation, depending on whether the learner views the second language group as a referenсе group or not. Both types involve social integration and therefore contact with the second language group, but the first type of learners wish to assimilate fully into its way of life, whereas the second do not. Schumann argues that these types of acculturation are equally effective in promoting L2 acquisition. The model recognizes the developmental nature of L2 acquisition and seeks to explain differences in learners' rate of development and also in their ultimate level of achievement in terms of the extent tо which they adapt to the target-language culture. Inter-group Model

We have already seen that Giles and his associates have been primarily concerned with exploring how inter-group uses of language reflect the social and psychological attitudes of their speakers. Giles and Byrne (1982), Beebe and Giles (1984), Ball, Giles, and Hewstone (1984), and Hall and Gudykunst (1986) have extended this approach to account for L2 acquisition. The inter group theory has become more complex over time in an effort to incorporate the results of ongoing research about what factors influence inter-group linguistic behaviour. The account below is based primarily on Giles and Byrne's original formulation.

The key construct is that of ethnolinguistic vitality. Giles and Byrne identify a number of factors that contribute to a group's ethnolinguistic vitality. They then discuss the conditions under which subordinate group members (for example, immigrants or members of an ethnic minority) are most likely to acquire native-like proficiency in the dominant group's language. These are: (1) when in-group identification is weak or the LI does not function as a salient dimension of ethnic group membership, (2) when inter ethnic comparisons are quiescent, (3) when perceived in-group vitality is low (4) when perceived ill-group boundaries are soft and open, and (5) when the learners identify strongly with other groups and so develop adequate group identity and intra-group status. When these conditions prevail, learners experience low ethnolinguistic vitality but without insecurity, as they are not aware of the options open to them regarding their status vis-a-vis native-speaker groups. These five conditions are associated with a desire to integrate into the dominant out-group (an integrative orientation), additive biIingualism, low situational anxiety, and the effective use of informal contexts of acquisition. The end result is that learners will achieve high levels of social and communicative proficiency in the L2.

Learners from minority groups will be unlikely to achieve native-speaker proficiency when their ethnolinguistic vitality is high. This occurs if (1) they identify strongly with their own in-group, (2) they see their in-group as inferior to the dominant out-group, (3) their perception of their ethnolinguistic vitality is high, (4) they perceive in-group boundaries as hard and, closed, and (5) they do not identify with other social groups and so have an inadequate group status. In such cases, learners are likely to be aware of 'cognitive alternatives' and, as a result, emphasize the importance of their own culture and language and, possibly, engage in competition with the out-group. They will achieve low levels of communicative proficiency in the L2 because this would be seen to detract from their ethnic identity, although they may achieve knowledge of the formal aspects of the L2 through classroom study. Socio-educational Model

Gardner's Socio-educational Model reflects the results of work begun a McGill University in Montreal in the 1950s and still carried on today. Unlike the other two models, which were designed to account for the role that social factors play in natural settings, in particular majority language contexts, Gardner's model was developed to explain L2 learning in classroom settings in particular the foreign language classroom. It exists in several versions (Gardner 1979; 1983; and 1985). The following account is derived from the 1985 version.

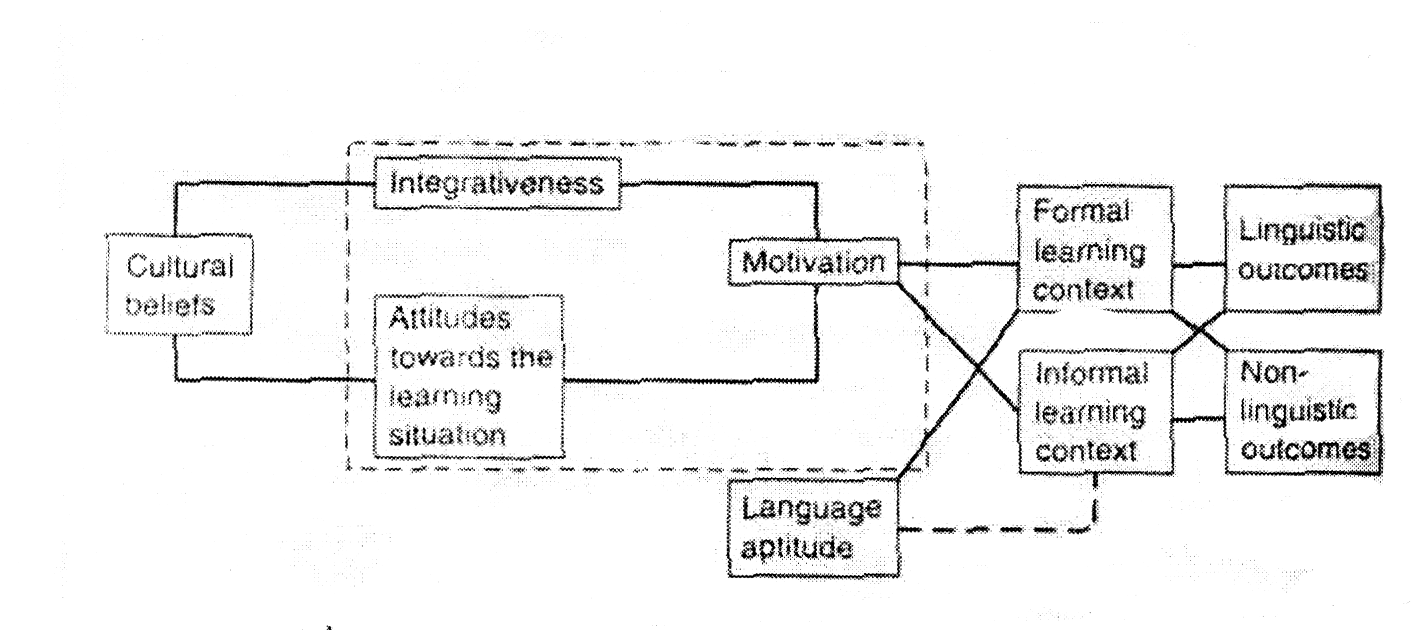

The model, which is shown schematically in Figure 1, seeks to interrelate four aspects of L2 learning: (1) the social and cultural milieu, (2) individual learner differences, (3) the setting, and (4) learning outcomes. The basis of the model is that L2 learning — even in a classroom setting — is not just a matter of learning new information but of acquiring symbolic elements of a different ethnolinguistic community. (Gardner 1979:193).

Figure 1 Socio-educational model

The social and cultural milieu in which learners grow up determines their beliefs about language and culture. In monolingual settings such as Britain and the United States, the prevailing beliefs are likely to be that bilingualism is unnecessary and that assimilation of minority cultures and languages is desirable. In bilingual settings such as Canada both bilingualism and biculturalism may be encouraged. Gardner identifies a number of variables that result in individual difference: they are motivation and language aptitude. The learners' social and cultural milieu determine the extent to which they wish to identify with the target-language culture (their integrative motivation) and also the extent to which they hold positive attitudes towards the learning situation (for example, the teacher and the multiinstructional programme). Both contribute to the learners' motivation, influencing both its nature (how integrative it is) and its strength. Motivation is seen as independent of language aptitude (the special ability for learning languages). Whereas motivation has a major impact on learning in both formal and informal learning contexts, aptitude is considered to be important only in the former, although it can play a secondary role in the latter. These two variables (together with intelligence and situational anxiety) determine how the learning behaviours seen in different learners in the two contexts and, thereby, learning outcomes. These can be linguistic (L2 proficiency) and non-linguistic (attitudes, self-concept, cultural values, and beliefs). Gardner, Lalonde, and Pierson (1983) and Lalonde and Gardner (1985) have investigated this using a statistical technique known as Linear Structural Analysis, which claims to be able to identify causal paths and not merely correlations among variables. These studies provide support for the view that factors in the social and cultural milieu are causally related to attitudes (integrativeness) which in turn are causally related to motivation and via this to achievement. Interpretation of the findings

According to the model chosen there was created a questionnaire (see Appendix 1) and there were two respondents chosen. The questionnaire was done basing on the four aspects of L2 learning: (1) the social and cultural milieu, (2) individual learner differences, (3) the setting, and (4) learning outcomes. The questions were designed to reveal the inner essence of the fields. As the aim of the research was to prove that the Socio-educational model is applicable to existing educational settings and that it functions effectively we agreed to offer the questionnaire to a non-native speaker of Russian (Mr.X) and to a non-native speaker of English (Mrs.Y). The choice provided the cross-examination of the problem. The working language was English. There were obtained the following results.

The respondents were of the same age and present social status, though they differ in their background – home country, parents’ occupation and cultural-educational background. One of the respondents felt the reluctance of minority language students at school to integrate into the educational community, underlining their “socializing only in their own groups”. Both respondents support the idea of teaching L2 to children without the constraint. They encourage bilingualism thus demonstrating their openness to the target language culture and positive attitude towards the learning situation.

The difference in educational setting – the lengths of studying languages (Mrs.Y –35 years all in all, 13 academic years of learning, all the rest of acquiring English; Mr.X only acquiring (no formal learning) Russian) results in different language aptitude – from Proficient to Elementary user. A heavy work schedule and rather a reduced ability to memorize new words were mentioned as factors which prevent from effective learning. Natural setting was called as the help for acquiring language. The willingness and the necessity to communicate were among the reasons that motivate to study a language. Thus we can establish difference in the learners.

The background knowledge of the country of the target language were absolutely different for the respondents, varying from “feeling at home” (Mrs.Y, about the USA) and “Very little is known about Russia in the USA” (Mr.X, about Russia). The present employment of the respondents is the same: TPU. We may conclude that the setting –natural or educational – is important for the stage of learning a language: educational (regular formal classes are better at the beginning of language learning, natural setting is better for acquiring or “picking up” a language at the high level of proficiency).

Both respondents are successful in second language acquisition and second culture acquisition as they are able to communicate in the target language (though to a different extent) and cope with cultural misunderstandings. Conclusion

The following are some of the major conclusions to be drawn from this exploration:

1 There is a biological timetable for optimal language learning which stymies the efforts of adolescents and adults to acquire language. But if they study systematically, they can be the fastest language learners in all areas except pronunciation due to their better reasoning to achieve an analytical understanding of the new language being studied.

2 Social factors have a general impact on the kind of learning that takes place, whether informal or formal. Both types can occur in natural and educational settings but there is a tendency for informal learning to occur in natural settings and formal in educational settings (particularly in foreign language classrooms).

3 There is no evidence that social factors influence the nature of the processes: responsible for interlanguage development in informal learning. There is ample evidence to suggest that they affect ultimate L2 proficiency, whether this is measured in terms of BICS or CALP.

4 The relationship between social factors and L2 achievement is an indirect rather than a direct one. That is, their effect is mediated by variables of a psychological nature (in particular attitudes towards to the target language, its culture and its speakers) that determine the amount of contact with the L2, the nature of the interpersonal interactions learners engage in and their motivation.

5 Regarding the role of specific social factors, few definite conclusions are currently possible. There is some evidence to suggest that greater success in L2 learning will be observed in younger rather than older learners, females rather than males, middle class rather than working class people and in learners whose ethnolinguistic vitality is such that learning the L2 is not perceived as a threat to their ethnic identity. In each case, however, exceptions have been reported. Many learners may not be targeted on the standard dialect of the target language. This suggests that measuring progress in terms of learners' approximation to the norms of the standard dialect — the normal procedure in SLA research — may be misleading.

Thus we may conclude that Socio-educational model functions effectively in the given educational settings. Appendix

Description of respondent

Personal information

Name: Nationality:

Age: Native language:

|

Questions |

Answers |

|

The social and cultural milieu Where do you live (home country)? What are/were your parents? Was the group of learners you studied at school/Uni a multinational one? If yes, how did you feel there? What did you feel towards your non-native language classmates? What do you think of teaching L2 to children? What is your attitude to bilingualism? Individual learner difference Do you speak Russian/English? How long have you been studying Russian/English? Why? Is your learning successful? Have you noticed any changes in the process of L2 acquisition while living in L2 country? What are the main obstacles which prevent you from effective L2 effective L2 learning? What helps you to acquire L2? What would you like to change? What environment do you consider better for your Second language (SLA)? Second culture acquisition (SCA)? What role, do you think, does motivation play in your SLA? The setting What were the assumptions you have made before coming to Russia? (l-ge, weather, traditions, people) What top ten words do you associate with Russia? Why have you chosen Russia to come? Where do you work now? Learning outcomes Can you give examples of a successful SLA, SCA? Unsuccessful SLA, SCA? |

|

References:

Beebe L., 'Inpu'f: choosing the right stuff in S. Gass and C. Madden (eds.), In-1, put in Second Language Acquisition (Newbury House, 1985).

Bickerton, Derek. Roots of Language. Ann Arbor, MI: Karoma Publishers, 1981.

Brown, H. D. (1994). Principles of Language Learning and Teaching (2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall Regents, 1994.

Cummins J., 'Language proficiency and academic achievement in J. Oiler (ed.), Issues in Language Testing Research (Newbury House, 1983).

Cummins, J. (1979). "Cognitive/academic language proficiency, linguistic

Cummins, Jim. “Empowering Minority Students: A Framework for Intervention.” Harvard Educational Review 56 (Fall 1986): 18-36.

Ellis, Rod. Understanding Second Language Acquisition. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall Regents.

Guiora, Alexander et al. “Construct Validity and Transpositional Research: Toward an Empirical Study of Psychoanalytic Concepts.” Comprehensive Psychiatry 13 (1972): 139-150.

Krashen, S. (1981) Second Language Acquisition and Second Language Learning.

Krashen, Stephen. Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition.Oxford: Pergammon Press, 1982.

Lenneberg, Eric. The Biological Foundations of Language. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1967. Oxford: Pergamon Press.Papers on Bilingualism, 19, 197-205.

Rubin, J. (1975). “What the Good Language Learner Can Teach Us.” TESOL Quarterly 9 (Fall 1975): 41-51.

Schumann, John. “Research on the Acculturation Model for Second Language Acquisition.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development (1986): 379-392.

Snow, Catherine and M. Hoefnagel-Hohle. “Age Differences in Second Language Acquisition.” Second Language Acquisition. Rowley, Mass.: Newbury House, 1978.

Strozer, Judith. Language Acquisition After Puberty. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Books, 1994.