It’s clear that repetition influences affective responses to social stimuli. According to the previous research familiar faces appear happier than novel faces in adults. Other study showed that 9 months old infants can associate own-race faces with happy music. These findings lead us to a question when this phenomenon starts to appear. The current study has examined whether 6–8 and 9–10 months old Asian infants could correlate the different emotional voice (happy or angry) with familiar or unfamiliar neutral female faces by using eye-tracking technique. The results show that only 9–10 months old infants can associate familiar faces with happy voice and unfamiliar faces with angry voice, not 6–8 months old infants.

Keywords: infants, face processing, facial experience, facial emotions processing.

1. Introduction

Experience plays a crucial role in the development of face processing in infancy. With increased experience, infant face-processing ability not only improves but also becomes specialized to process the types of faces experienced most frequently [1]. But how experience influences face processing bias in now unclear.

Previous studies have shown that unreinforced repetition (familiarization) influences affective responses to social stimuli. Familiarization (via unreinforced repetition) associates the stimulus with an absence of negative consequences [2] and reduces uncertainty, and repetition facilitates processing [3] and such fluency is experienced as positive [4]. Carr, Brady, and Winkielman (2017) found that familiar faces appear happier than novel faces in adults. The findings lead us to a question, at what age this phenomenon start to appear?

Previous studies found that infants tend to associate familiar faces with positive emotional signals. For example, infants can associate happy facial expression of their mother with happy voices, but when faces are strangers’ — they do not [5]. Moreover, research conducted by Xiao, Quinn, Liu, Ge, Pascalis and Lee (2017) has shown that 9 months old infants associate own-race faces with happy music and other-race faces with sad music, but not 6 months old infants [6]. We think that familiarity maybe enhances responses to positive features and it also happens in 6–10 months old infants.

Therefore, the current study will explore the following two questions by exposing 6–10 months old infants to familiar and novel faces paired with happy or angry emotional voices: 1) Do infants look longer at the familiar face after the positive vocal stimuli? 2) Is there a developmental difference in infancy in recognition of the familiar faces paired with positive stimuli?

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Infants were randomly assigned to the experiment, before which their caregivers gave informed consent. Effective subjects were 35 healthy Asian babies aged 6–10 months old: 13 infants of 6–8 months old (M=195.15 days, SD=18.66 days, age range: 178–242 days, seven males) and 22 infants of 9–10 months old (M=259.18 days, S=19.14 days, age range: 243–311 days, eleven males). Four subjects were excluded: one didn't receive enough familiarization time during the familiarization phase, during testing three subjects the error in the program of Tobii occurred. The babies who participated in the experiment were all from a public health service hospital in Xiasha, Hangzhou, and were all healthy. Parents volunteered to bring their children to participate in the experiment.

2.2. Stimuli

2.2.1. Face stimuli

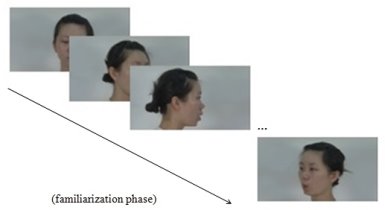

Face stimuli during familiarization phase includes videos of seven Asian females (age range: 22–25), each type of videos includes different acting behaviors (such as counting, chewing, gazing to different sides (left, right, up, down), head inclining to the left and to the right) and different head turns (front view, side view (left and right), 3/4 view (left and right)), all with neutral facial expressions. These stimuli were taken from a set of videos developed by Xiao, Quinn, Liu, Ge, Pascalis and Lee, 2017. The emotional valence of the face stimuli was previously validated by twelve Asian adults (age range: 22–28 years old, 6 males). A 7-point Likert scale was used (1: very negative, 4: neutral, 7: very negative). The faces didn’t differ significantly from neutral emotional valence (M=4.05, SD=0.40). In addition, it was previously ensured by Xiao, Quinn, Liu, Ge, Pascalis and Lee that all the actors moved and spoke at the same tempo, which was achieved by asking the actors to count, chew, gaze or incline a head at a steady pace. The reason why we presented moving face videos in the current experiment, instead of static face images, was because prior studies have shown that infants tend to perceive neutral static faces as emotionally negative. Each female actor maintains neutral emotions, thus eliciting the possibility for the infants to be prejudiced during the test phase. The videos were edited to ensure that faces were similar in size, and placed on a light color background. Each video contains a grey background. All the videos do not include the audio. The order of acting behaviors is randomized, while the order of head turns is randomized also but includes all 5 angles. (Figure 1.) The duration of each video is equal (M=10.86 s, SD=2.5 s). Regarding the fact that 6–10 months old infants require at least 42.67 s to familiarize a novel face successfully, 5 videos in total were exposed to the subjects of the current experiment, which makes at least 50 s of familiarization for each subject to be exposed to. If an infant stops looking at the monitor, video stops playing as well, thus letting each of the infant to receive the necessary time for the familiarization.

Figure 1. Moving neutral Asian female faces include five views: frontal, ¾ (left and right), and profile (left and right). Each video is equal in duration (M=10.86 s, SD=2.5 s)

Videos were shot by camera Sony and edited in Adobe Premier Pro afterwards. Between the video the bright cartoons are played to attract infant’s attention, each cartoon lasts 10 s and can be stopped as soon as infant draws his attention back to the monitor. During the test phase infants are exposed simultaneously to the two different images of female actors with frontal views. The three images with frontal view of each female were extracted from the videos form the familiarization phase. The images were captured in moments when female actors didn't produce any movements. The background of the images is black. All the images are similar in size (width: 546 pixels, height: 647 pixels).

2.2.2. Emotional vocal sound

During the test phase each infant is exposed both to the audial and visual stimuli. Right after the end of the familiarization phase an infant can hear either positive (happy) or negative (angry) voice, the order of which is counterbalanced. At this time a white flickering circle appears. The sound lasts for 3 s. One happy and one angry emotional vocal sound were selected from a set of emotional vocalizations developed by Sauter, Eisner, Ekman, and Scott (2010) and validated by adult participants across different cultures. Importantly, these sounds have been validated with infants as well: Previous infant studies with the same emotional vocal sounds showed that 6.5-month-old infants could reliably associate the vocalization of different emotion with corresponding affective body postures [7], confirming that infants starting at 6.5 months of age are able to process the emotional contents of these emotional vocal sounds. The average loudness of the happy and angry vocalizations was equalized to 65 dB with Adobe Audition CC 2017.

2.3. Procedure

Parents brought their babies into the laboratory and were told to take precautions. After entering the laboratory, the baby is sitting on the parent's leg, 60cm away from the eye tracker. The first experimenter stands behind the baby to facilitate the adjustment of the baby position, the second experimenter instrument operation in the background. Firstly the subjects were calibrated. In the beginning the screen presents a cartoon image that accompanies the sound, randomly presented in 5 positions (center of the screen and four corners) of the screen. The baby must reach the calibration standard (at least 4 positions per eye) before entering the formal experiment, calibration up to 3 times, if 3 times after all failed, the test exit experiment.

Familiarization phase

After the calibration, the familiarization phase starts. An infant is exposed to five videos of the same Asian female actor with five views (frontal, profile (left and right), and ¾ (left and right)). Each trial includes one video, which makes in total five trials in the familiarization phase. Across the five trials each video include one of the different types of actor’s behavior (such as counting, chewing, eye gazing to different sides (left, right, up, and down) and head incline (left and right), the order of which is randomized. All the videos include neutral facial expressions and do not include audio. The experiment was programmed in a way that each infant will receive the necessary amount of time (which is 48 s minimum) to familiarize a novel face. Each video lasts in average 10.86 s (SD=2.5 s), and it makes not less than 50 s in total. If an infant doesn't pay attention to the monitor, the video stops and start playing once an infant look back at the monitor. Between all five videos an infant is exposed to a colorful cartoon that lasts 10 s in total and can be stopped at any time by the experimenter. (Figure 2.)

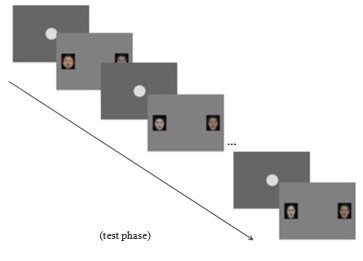

Figure 2. Familiarization phase includes five trials, each of one consists of the video of a neutral moving Asian female face. Average duration of each video is 10.86 s (SD=2.5 s). The test phase includes 16 trials, each of one consists of a vocal emotional sound (happy or angry), and a set of two images with frontal view at a both side of the monitor: novel female face and familiarized female face. The duration of the sound is 3 s, the images keep displaying during 3 s as well.

Test phase

After the familiarization phase the test phase starts. Firstly, an infant is exposed to the audio stimuli, which is either positive (happy) or negative (angry) voice. The sound lasts for 3 s during which the flickering white circle appears in the center of the monitor. After the audio stops playing, an infant sees two images of the same size located in the different sides of the monitor of female face: one is a novel face, the other is the familiarized face during the familiarization phase face. In each trial the novel female face is new, each of one was extracted from the videos used in the familiarization phase. The order of the location of the novel face is randomized. The two images (novel and familiarized) keep staying at the display for 3 s after which a colorful cartoon is played (the same as in the familiarization phase) to draw infant’s attention and can be stopped by the experimenter at any time. After it the consequence starts from the beginning. The order of positive and negative voices is randomized. The test phase includes 16 trials.

3. Results

Preliminary examination of the data revealed no significant gender differences for stimuli or participants, so the data were combined for further analysis.

Familiarization phase

To examine whether infants habituated the faces, we calculated the looking time during the familiarization phase for 6–8 months old age group (M=53.72 s, SD=38.95 s) and 9–10 months old age group (M=55.52 s, SD=12.18 s). Both age groups received the necessary amount of time to familiarize a face, which is 54.62 s in average. In Kelly D., et al. (2007) article the familiarization time for 6-month-old was 42.67 s and for 9-month-old was 38.88 s to get habituation, and infant could recognize faces [8]. In the current research the familiarization time is longer and infants’ familiarization time was thought long enough.

Test phase

Familiar face

To calculate the difference in mean proportional time to the familiar face in angry voice or happy voice conditions, we conducted A repeated-measured ANOVA for the familiar face in total 16 trials: 2 (emotion: happy vs. angry) x 2 (age group: 6–8 months old vs. 9–10 months old), the emotion variable was within-subject and the age group variable was between-subject. There was neither main effect of age (F(1,33)=0.00, p=0.992, η2=0.000), nor main effect of emotion (F(1,33)=0.17, p=0.423, η2=0.020). We also found no interaction between emotion and age (F(1,33)=1.53, p=0.224, η2=0.045). The results showed that infants could not relate familiar faces to happy voice in total trials.

We took first 4 and last 4 trials of the test phase into account. The reason why we did it, is because the separation of the first 4 and last 4 test trials can reveal the dynamic changes in infants' looking behaviors as infants gets more and more familiar with the familiar face. At the beginning of the test trials, even the familiar face might look novel to the infants, because this was the first time they saw the static picture of this female actor, previously, infants were exposed to moving face videos. In this case, they might not show any association between emotional sounds and face familiarity at this stage. With the progress of the test trials, infants got more and more familiar with the familiar face, but the novel face remains new to them, because we always used a new face for each test trial. At this late stage, infants might be more likely to show difference in associating emotional signals with familiar and unfamiliar faces.

With regard to why choosing 4 trials, this is because we have two emotional sounds (happy and angry) and two spatial layouts for the two faces (familiar face on the left and familiar face on the right), which gives us 2*2 = 4 trials. In other words, 4 trials is the smallest unit to calculate a reliable looking preference for each emotional sound.

The data was shown in Table 1. We conducted A repeated-measured ANOVA for the familiar face: 2 (emotion: happy vs. angry) x 2 (age group: 6–8 months old vs. 9–10 months old) x 2 (trials: first 4 vs. last 4), the emotion variable and trials were within-subject, the age group variable was between-subject, the result showed no main effects (main effect of emotions: (F(1,33)=0.84, p=0.364, η2=0.03; main effect of age group: F(1,33)=0.20, p=0.660, η2=0.01; main effect of trials: F(1,33)=0.60, p=0.443, η2=0.05). There was neither significant effect for interaction between emotion and age (F(1,33)=1.68, p=0.203, η2=0.049), nor for three interactions between emotion, age and trials (F(1,33)=9.96, p=0.348, η2=0.027). But we found two interactions: between age and trials (F(1, 33)=5.11, p=0.030, η2=0.134) and between emotion and trials (F(1,33)=5.83, p=0.021, η2=0.15).

Table 1

Proportional looking time to the familiar face, M±SD (%)

|

Age group |

Vocal sound |

First 4 trials |

Last 4 trials |

Total 16 trials |

|

6–8 months old |

Angry |

54.23±20.12 |

39.6±9.60 |

47.9±11.33 |

|

Happy |

46.06±17.55 |

45.18±16.95 |

46.47±12.97 |

|

|

9–10 months old |

Angry |

43.69±17.48 |

44.49±17.86 |

43.81±15.65 |

|

Happy |

48.33±15.07 |

55.10±17.65 |

50.64±13.69 |

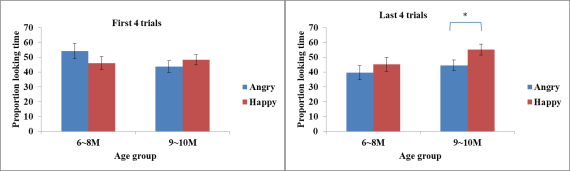

Though there is no three interaction between emotions, trials and age group, we are interested in the developmental change, thus we conducted a paired-samples t-test where we used mean proportional looking time to the familiar face as a dependent variable and happy-voice condition vs. angry-voice condition as an independent variable for each age group in first or last 4 trials condition. The result was shown in Figure 3.

Regarding the age group of 6–8 months paired t-tests revealed that, there was no significant difference of the mean proportional looking time neither for the first 4 trials, (Mangry=54.23 %, SDangry=20.12 %, Mhappy=46.05 %, SDhappy=17.55 %, t(12)=1.160, p=0.135) nor for the last 4 trials (Mangry=39.60 %, SDangry=14.6 %, Mhappy=45.18 %, SDhappy=16.95 %, t(12)= -1.012 p=0.170). The results showed that 6–8 months old infants could not relate familiar faces to happy voice in total trials.

The paired t-tests revealed no significant difference for the first 4 trials for 9–10 months old age group, (Mangry=43.69 %, SDangry=17.48 %, Mhappy=48.33 %, SDhappy=15.07 %, t(14)= -0.689, p=0.166). However, there was a significant difference for the age group of 9–10 months with 4 trials taken into account, (Mangry=44.49 %, SDangry=17.86 %, Mhappy=55.10 %, SDhappy=17.65 %, t(14)= -1.892, p=0.024). These results showed that 9–10 months old infants could relate familiar faces to happy voice in last 4 trials.

Figure 3. Each panel presents proportion looking time at the familiar face under either happy voice or angry voice conditions. First graph presents difference between 6–8 months old and 9–10 months old age groups in first 4 trials. Second graph presents difference between 6–8 months old and 9–10 months old age groups for last 4 trials. The asterisk indicates that the difference was significant

Unfamiliar face

To calculate the difference in mean proportional time to the unfamiliar face in angry voice or happy voice conditions, we conducted A repeated-measured ANOVA for the unfamiliar face in total 16 trials: 2 (emotion: happy vs. angry) x 2 (age group: 6–8 months old vs. 9–10 months old), the emotion variable was within-subject and the age group variable was between-subject. There was no interaction between emotion and age (F(1,33)=1.24, p=0.274, η2=0.013), We found neither main effect of emotion (F(1,33)=0.43, p=0.515, η2=0.036).l, nor main effect of age (F(1,33)=0.25, p=0.876, η2=0.001). These results showed that infants could not relate unfamiliar face to happy voice in all the trials.

The same as for the familiar faces, first 4 trials and last 4 trials were taken into account. The data was shown in Table 2. We conducted A repeated-measured ANOVA for the unfamiliar face: 2 (emotion: happy vs. angry) x 2 (age group: 6–8 months old vs. 9–10 months old) x 2 (trials: first 4 vs. last 4), the emotion variable and trials were within-subject, the age group variable was between-subject, the result showed no main effects: main effect of emotions: (F(1,33)=0.79, p=0.379, η2=0.02; main effect of age group: F(1,33)=0.17, p=0.682, η2=0.05; main effect of trials: F(1,33)=1.79, p=0.469, η2=0.01). There was neither significant interaction between emotion and age (F(1,33)=1.68, p=0.190, η2=0.051), nor for three interactions between emotion, age and trials (F(1,33)=0.81, p=0.375, η2=0.024). But we found two interactions: between age and trials (F(1, 33)=4.91, p=0.034, η2=0.130) and between emotion and trials (F(1,33)=5.61, p=0.024, η2=0.15).

We also conducted a paired-samples t-test where we used mean proportional looking time to the unfamiliar face as a dependent variable and happy-voice condition vs. angry-voice condition as an independent variable, and we found that there was no significant difference for the age group 6–8 months old neither in the first 4 trials (Mangry=45.77 %, SDangry=20.12 %, Mhappy=53.95 %, SDhappy=15.07 %, t(34)=1.160, p=0.269), nor in the last 4 trials (Mangry=60.40 %, SDangry=9.60 %, Mhappy=54.82 %, SDhappy=16.95 %, t(12)=0.964, p=0.354). The results showed that 6–8 months old infants do not associate unfamiliar face neither with happy voice nor with angry voice.

We found that there was no significant difference for the age group 9–10 months old in the first 4 trials (Mangry=56.31 %, SDangry=17.48 %, Mhappy=51.67 %, SDhappy=15.07 %, t(14)= -0.031, p=0.976), but there was a significant difference in the last 4 trials (Mangry=55.51 %, SDangry=17.48 %, Mhappy=44.90 %, SDhappy=17.65 %, t(21)=2.098, p=0.049). The results showed that 9–10 months old infants could relate unfamiliar faces to angry voice in last 4 trials.

Table 2

Proportional looking time to the unfamiliar face, M±SD (%)

|

Age group |

Vocal sound |

First 4 trials |

Last 4 trials |

Total 16 trials |

|

6–8 months old |

Angry |

45.77±20.12 |

60.40±9.60 |

52.10±11.33 |

|

Happy |

53.95±17.55 |

54.82±16.95 |

53.53±12.97 |

|

|

9–10 months old |

Angry |

56.31±17.48 |

55.51±17.86 |

56.19±15.65 |

|

Happy |

51.67±15.07 |

44.90±17.65 |

50.60±13.69 |

- Discussion

The current study using eye-tracking technique examined whether 6–10 month old infants could related positive features with familiar faces or not. Firstly, we found that 6–8 months old infants did not look longer at familiar faces in happy voice condition, neither for unfamiliar faces in angry voice condition. This outcome indicates that infants initially did not associate familiar face with voice emotional valence, suggesting that infants are not biologically predisposed to associate familiar and unfamiliar faces with voices of different emotional valence.

Our second major finding is that 9–10 months old infants looked longer at familiar faces in happy voice condition in last 4 trials. This outcome indicates that our predictions were right: at the beginning of the test phase (first 4 trials) the familiar face looks new to infants, because this is the first time they are exposed to the static picture of the female actor they saw in the familiarization phase in the videos. By the end of the test phase (last 4 trials) infants already familiarized with the static picture of the familiar face, not with the static picture of the novel face, because we used a new female actor’s face in each trial.

This developmental change in infants’ looking behavior shows that only for 9–10 months old infants familiar face looks happy, not for 6–8 months old infants.

These findings are consistent with the previous study of Evan W. Car, Timothy F. Brady, and Piotr Winkielman (2017) where familiar faces looked happier for adults.

However, our findings also showed that 9–10 months old infants can associate unfamiliar faces with negative valence, as they looked longer at unfamiliar faces in angry voice condition. These results do not correspond to the hedonic-skew framework hypothesis. These findings are consistent with the the study of Xiao N Q, Pascalis O, Lee K, et al. (2017) where 9 months old infants associated own-race faces with happy music and other-race faces with sad music.

To explain this phenomenon we can refer to the fact, that infants are mostly exposed to the positive emotions in real life situations, they might do not expect the negative emotions to appear, thus associating it with negativity. One possible explanation is stranger anxiety. Extensive studies showed that 9 months old infants show wariness to strangers [7], and this stranger anxiety develops with age within the first year of life [9]. Infants are nervous when they meet strangers. Thus they are easy to relate the angry voice to the unfamiliar face.

Different from previous studies that they found experience influence face processing bias, the current study tried to explore how experience influence infants face processing bias. Based on Xiao et al.(2017) finding, they explained the mechanism of experience that the reason why infants associate familiar faces with happy music is because infants are primarily exposed to familiar faces which mostly pose positive expressions and deliver joyful infant-direct speech. Owing to the experience with familiar faces and happy music, infants develop a specific association to perceive familiar faces as emotionally positive entities. Our finding had a progress to test the hypothesis that infants correlated familiar faces with happy voice and unfamiliar faces with angry voice.

Theoretically, our findings show for the first time which emotions infants process by exposing to familiar faces, moreover, it was shown for the first time that repeated exposure enhances the perceived happiness of facial expressions in infancy.

However, the current research has some limitations. Firstly, the number of subjects for the age group of 6–8 months old is not enough equal to the age group of 9~10 months old. Though the number of 13 is enough for test the hypothesis, there will be good if there are enough subjects.

Secondly, video stimuli in the familiarization phase have no voice, which does not correspond to the real life situations, where infants are always exposed to faces with voices simultaneously. In the future study, we can use voice in the familiarization phase for the video stimuli.

Furthermore, the future study could go on with exploring the mechanism of experience, especially for familiar faces. More and more researchers are interested in how people process a face from strange to familiar and what information is recruit in face processing. For adults, the studies have found that the conceptual information is more important than perceptual information [10]. But in our study, we found that simple repetition exposing made infants relate positive feature with familiar faces. This finding implicated that for infants perceptual information is as important as conceptual information. In future study, we will go on with explore which information is important for infants processing a face from strange to familiar.

References:

- KAHANA-KALMAN R, AND WALKER-ANDREWS A S. The role of person familiarity in young infants’ perception of emotional expressions [J]. Child Development, 2001, 72: 352–369.

- ZAJONC R B. Mere exposure: A gateway to the subliminal [J]. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 2001, 10: 224–228.

- BORNSTEIN R F, & D’AGOSTINO P R. The attribution and discounting of perceptual fluency: Preliminary tests of a perceptual fluency/attributional model of the mere exposure effect [J]. Social Cognition, 1994, 12: 103–128.

- WINKIELMAN P, SCHWARZ N, FAZENDEIRO T, & REBER R. The hedonic marking of processing fluency: Implications for evaluative judgment. In J. Musch & K. C. Klauer (Eds.) [J]. The psychology of evaluation: Affective processes in cognition and emotion, 2003: 189–217

- XIAO N Q, PASCALIS O, LEE K, ET AL. Older but not younger infants associate own- race faces with happy music and other- race faces with sad music [J]. Developmental Science, 2017, 21(2): 1–10.

- PASCALIS O, KELLY D J. On the development of face processing [J]. Perspective in Psychological Science, 2009, 4: 200–209.

- BRONSON G. Infants’ reactions to unfamiliar persons and novel objects [J]. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 1972, 37: 1–46.

- KELLY D J, LIU S, LEE K, et al. Development of the other-race effect during infancy: evidence toward universality? [J]. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 2009, 104(1): 105–114.

- CAMPOS J, EMDE R, GAENSBAUER T, HENDERSON C. Cardiac and behavioral interrelationships in the reactions of infants to strangers [J]. Developmental Psychology, 1975, 11: 589–601.

- LINOY S, GALIT Y. The roles of perceptual and conceptual information in face recognition [J]. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 2016, 145(11): 1493–1511.