The disruption from the COVID 19 pandemic has spread into every sector of the global economy, disrupting consumers, retailers and producers alike. There were fears that as the virus reduces or removes demand for certain goods, standard measures of inflation could mask soaring prices for essential items undergoing supply chain disruption or shortages.

During the lockdown, which is the most effective way against spread of coronavirus, there can be seen upward trend in consumer prices index. Economy of many countries feel that trend because of higher demand for primary consumer goods. As lockdown slows, even stops, small enterprises` activity there can be hardly find major suppliers of goods.

The immediate response to the virus has created a simultaneous sharp fall in both supply and demand. Whilst the balance of supply and demand shifts is not the same across all sectors, so that major relative price shifts are occurring, it seems unlikely that overall inflation (almost impossible to measure accurately now anyway) has risen.

Covid-19, however, is not a conventional economic threat. When people stop spending, growth slows, and inflation falls. But when supply is constrained, prices can accelerate even as the economy wobbles. Some governments try to finance the public due to help them survive during the shock. Such form of social supply affects the money supply in the country’s economy, it will increase purchases as needed.

Governments` social supply and protection of public based on easy money policy. But if we distribute money for nothing, they will immediately lose their purchasing power. They will immediately devalue, inflation will increase, devaluation will occur. The principal problem with money financing (printing) is that it tends to set an inflationary spiral in motion. In reality, however, forecasting about the inflation rate is not high enough. And there is the matter: any government may not support the whole economy and public consumption.

Policymakers facing temporary supply shocks must reassure the public that growth and inflation will eventually return to normal—as modern central banks now try to do when oil prices spike.

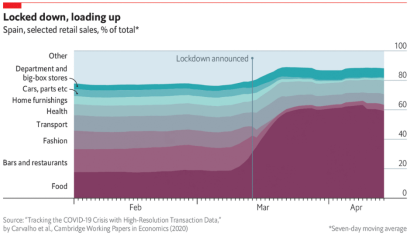

According to surveys to identify a basket of goods and services that represents the spending habits of a “typical” household, lockdowns imposed to curb the covid-19 pandemic have thrown this process out of whack. People’s spending has shifted dramatically. A higher proportion of spending is surely going towards groceries (even if the early dash for toilet paper, pasta and flour seems to have subsided) and online entertainment.

Obviously, rise of CPI has a large effect on inflation calculations. However, lockdown did not impact on CPI basket entirely. After the lockdown, size consumption of food raised as three times as the volume of it before. People started to spend less money for fashion, shopping, bars and restaurants because of quarantine. General volume of consumption showed an upward trend.

The key point is that, all the calculations for short-time period. What if covid-19 is out of control and there cannot be seen any vaccine more than two years? We say two years assuming that many governments can stay against the coronavirus about two years. Unlikely, there are undeveloped countries with their poor economy which already began to sink. The strongest economies cannot stand 2-years-period of lockdown. All of that is pessimistic idea, but possible.

On the other hand, the decline in foreign and domestic economic activity has an impact on the income of the population, leading to a significant reduction in demand for goods and services that do not belong to the group of most basic necessities in the consumer basket. The dynamics of growth in the prices of certain food and essential consumer goods under quarantine conditions is temporary, and the saturation of markets with these goods as a result of the release of a new crop of agricultural products in the coming months will help stabilize their prices.

Since March, in the world and in major trading partner countries as a result of intensified measures to combat the coronavirus pandemic, falling oil prices, declining demand forecasts of economic growth have been declining. There is also a certain downward trend in lending activity in the economy. Banks have extended the terms of repayment of loans to individuals and legal entities. This, in turn, leads to a certain reduction in their lending capacity by the inflow of cash to banks.

Looking farther down the road, the price of some things might rise on a more permanent basis after the pandemic due to protectionism or a greater focus on local supply chains over international trade.

Uncertainties remain about the extent and duration of the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on the economy. At the same time, central banks will continue to study in depth the nature of the factors and risks of inflation under the influence of external and internal conditions. And they will make appropriate decisions on the formation of inflation forecast dynamics.

Done right it could set the course of the economy for a generation and bring in the revenues to pay back the debt. The other choices are more austerity or high inflation.

Additionally, it is difficult to forecast about inflation targeting regime as the effectiveness of inflation targeting on lowering inflation is found to be quite heterogeneous. The performance of a given inflation targeting regime can be affected by country characteristics such as government's fiscal position, central bank's desire to limit the movements of exchange rate, its willingness to meet the preconditions of policy adoption, and the time length since the policy adoption.

In conclusion, effects of COVID-19 on inflation vary according to features of economy and monetary policy of countries. Current impact is not very significant. But everything will depend on how long this situation lasts.

References:

- http://www.economist.com/

- http://www.sciencedirect.com/

- http://www.thebanker.com/

- http://www.scopus.com/

- https://inflationdata.com/