The Article deals with the problem of lost and found identity of Koryo Saram.

Key words: Koryo Saram, identity, diaspora.

Untrustworthy, aliens, fools. In the late 1800s to early 1900s, all foreigners, including Koreans, were called these names in the former USSR. The Priamur governor-general, P.F Unterberger, once said, «I prefer a wasteland — a Russian wasteland to cultivated land which is Korean» [3, p. 47]. Ethnic Koreans were disliked and chased until they fully developed their recognition as «Koryo Saram». However, despite the name of «Koryo Saram», they still do not have an identity that defines who they exactly are. Are they Russians? Are they Koreans? Neither. Despite of all speculations based on historiography and fiction, the question of the lost identity of Koryo Saram is still open. As we know the core question in diasporic identity formation is conscious self-identification. That is why it is very important to listen to the voices of the Koryo Saram people. So, this paper is mainly based on an interview along with a public survey that I conducted among 54 Koryo Saram people, ranging from 16 to 76 years old [10].

The Ethnic Koreans' history began with a division of two periods: the Far Eastern period and r the post-deportation period. In the 1860s, the Koreans came about for the following reasons of migration: labor shortages and economic hardship. Aleksandr Leonidovich, a man I personally interviewed, is a lawyer currently living in Borovichi, Russia. Like many families back then, his own family «came to Primorsky krai back in the 19th century, approximately 1875...because of famine». [8] Many ethnic Koreans, like Aleksandr's family, immigrated to the land of Russia’s eastern coast called Primorsky Krai, which was the closest to Korea. Starting from a relatively small number of 10,137, in 1882, the population rapidly increased to about 32,380. Then came what is known as the «Korean Question», which the Governors established to forbid any more immigrants from coming to Russia. Not only that, but the ones who already settled in Russia were also transferred to the territory of Krai Koreans who were living in the Far Eastern territories lost all their supplies, money, and land. What's worse, their lands were given to the Russian settlers. By extension, the Russian-Korean convention on border relation was signed on Aug 20, 1888, turning Koreans into three different groups: ones who were granted Russian citizenship, who wanted to follow and adopt the laws to obtain citizenship, and the short-term who required labor contracts. From 1904 to 1905, the Russo-Japanese war began, which created countless of Korean migrants. Although the Koreans were kept in strict control, they still illegally emigrated to Russia through the Tumen River. They stayed in Vladivostok along the shores of the Amurskii and Usuriiiskii bays. By 1909 over 60,000 Koreans had settled in the Primorsky Krai.

Due to the innumerable Koreans, the Russian government started to mistrust Koreans. Unterberger, the priamur governor-general, was especially skeptical of Ethnic Koreans. After the Russo-Japanese war, not only was the relationship between Japan and Russia not in good terms but in 1910 Korea was also annexed by the Empire of Japan. In this case, governors such as Unterberger considered even the long-term Korean settlers as untrustworthy and Japanese spies. The hatred grew, and the migrants were sent out of the border regions and kept under strict control.

The Koreans, of course, did not remain still. As the 1917 October revolution occurred, many Koreans decided to stand by the Soviets, specifically, the Red Army. This was mostly because Korean workers considered the soviets as defenders of their oppressed peoples' rights and freedom: in short, freedom. Unfortunately, the hopes of liberty and the desire for sovereignty remained unattained dreams of the Korean settlers. The long legal migration process got out of hand. Two-thirds of the Soviet Koreans were not given Russian citizenship. Receiving Soviet citizenship was almost impossible for them. Hence, in 1923, only 1,300 out of 60,000 Koreans received Soviet citizenship [3, p. 87].

Despite not having citizenship, Koreans began to build their identities as best as they could. Through their effort, Koreans started to play significant roles in Russian society. They were positioned high within governments, could build their schools, and learn their languages. For instance, 105 of the new Soviets village were Korean as compared with the earlier 87 [2, 107]. Koreans were also incredible farmers in rice cultivation. They increased both the acreage under cultivation as well as the size of the harvests. Later, after their deportation the authorities in Uzbekistan would even offer them to work with the republics' rice farming lands; however, that was not put into action.

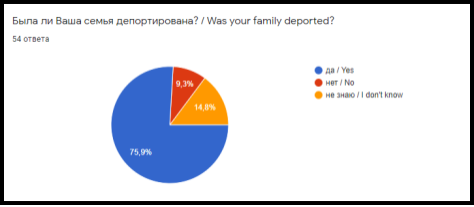

Their joys were short-lived. As Koreans slowly began to gain power, one of Aleksandr's grandfather's brothers was also « the member of the political organization in the red army» ; according to Alkesandr « he was very honored, respected, and also had a lot of awards for his revolutionary activities». However, « in 1936, he was arrested because of the idea of a spy in Japan». Not only that, but Aleksandr also says that «no one ever knew what happened to him after he was arrested since « he did not come back». [9]. A public survey that I conducted, with over 54 responses from people currently living in Russia with a variety of nationalities, claimed that the majority of its family members were severely faced by the oppression under Stalin.

Further aggravated, as Stalin held his position as a dictator, Koreans were treated as a separate phenomenon. The past struggles were nothing compared to Stalin's policy of deportation in 1937. It was as if Stalin paved a path for death for all those «aliens» living in Russia. The 75.9 % of the surveyors’ family members were also deported during the period of 1937.

Fig. 1. Survey results, August 2020

Koreans and other «aliens» had only three days to pack for their supplies. Same as Aleksandr's family, they « did not have time to pack (their) belongings or to sell things for money» and « only had time to take most important things and few documents». [9]. Then, immediately, the «aliens» were sent to the train known as the «ghost train». Millions of people died in that suffocating ride of more than a month. Dead bodies were rather thrown away than buried, born infants died shortly after, and starvation struck many people. Aleksandr's grandmother's sister also died during the way and was « buried on the way ». In context, Aleksandr states that « people buried their relatives in every single car» and «sometimes (they) could stop to bury them but most of the time people were forced to just throw the bodies away» [9]. Different groups were abandoned in varying stops, in which most Koreans were transported to Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

The territories that they arrived in were empty. There were some nomadic tribes living there; there were barely any shelters and short access to food either. Aleksandr's family members « were not given any home or dwelling places to live in». Their family and other people « had to dig special houses on the earth, called zemlyanka (earth hut)». These huts were opened, which made it almost impossible for them to survive in harsh conditions. The only thing that they were given was the ample vacant land that belonged to the state, which they had no choice but to cultivate. Aleksandr's family, for example, grew cotton. He states that «after a while, (their) Kolhoz in Kazakhstan became prosperous and rich». It was called «Zarya (dawn) kommunisma», which « in one year, could produce the record amount of cotton» [9].

Effectively, as the horrific deportation period passed, the desire for independence became more vital for the Koreans. The Koryo Sarams thought that their desire would be fulfilled if they highly supported the Soviet Union. Therefore, not much after the deportation, when WWII occurred, those Soviet Koreans wanted to fight alongside the Russian army. However, although some of them were allowed to fight for the Soviet Union, most people were denied since they were not 'Soviet citizens'. Through all those years, they were still considered as untrustworthy individuals. Those who could not fight for the nation were sent to labor camps or labor fronts, which caused countless deaths.

However, as mentioned, some of the Soviet Koreans fought with the Red Army because they had a firm belief it was their country and it was their duty to defend it. Unfortunately, that was not the case and things became worse after WWII. The few existing Korean schools were banned, their language was considered irrelevant, and even the Korean theater productions were delivering messages directly from Stalin. Language and identity started to diminish. Not only was the identity hampered, but due to the labor camps and the war, not many men survived, leaving only the women and children.

Despite the difficulties, believing that they experienced worse, the Soviet Koreans worked hard. They traveled to faraway regions to promote skills in rice cultivation and onion and watermelon farming. Their rice cultivation, mostly, was outstanding. As things started to arise, in 1953, Stalin died. Although it was a massive tragedy for the country, it was a chance to regain their national identity for the Koreans. As a result, during Ottepel (The Thaw), which appeared as a milder political regime, all «aliens» were set free and freely traveled around the world without any restrictions. Some went back to Korea; some went to Russia's main cities or to Primorsky kraia place where they originally lived; however, most of the Soviet Koreans stayed in the places of their former deportation — in Khazakstan and Uzbekistan.

During that era, Kobonjil came to existence — a farming activity in the pursuit of individual profit, distinctively created by the Koryo Saram. The Koryo Saram also established capitalism with their private sectors. This was established once the USSR crashed, as the currency changed, and the economy became less of collectivization. It benefited the Koryo Saram greatly since they could start private businesses that did not always have to do agriculture.

The collapse of the USSR in 1991 allowed the Koryo Saram to start searching for their true identity. Perestroika also known as the Revival came into existence. It was much more flexible than the Ottepal era, which, as mentioned above, permitted capitalism to exist. It was the time to ask themselves who they were in the country and who they wanted to be.

Well, they weren't aliens or strangers any more, but most Koryo Saram could not place themselves in a specified identity group; Were they Russian? Were they Korean? Most were ethnically Korean, but even ethnicity could be approached in different ways: primordialism, constructivism, and instrumentalism. The most well-known approach would be primordialism, which consists of elements like blood, history, and territory. Connected with more social aspects, constructivism is categorized with common myths, group identity, and solidarity. Combining both primordialism and constructivism, instrumentalism allows the group to choose their own ethnicity that most benefit them. Likewise, a social scientist, Robin Cohen, classifies the idea of home with three words: «solid, ductile, and liquid» [1, p.3]. Solid refers to the native land, otherwise the origin of the people; Ductile refers to a home in which people settle in or feel a sense of belonging; Liquid refers to the desire for home.

These aspects also come with the concept of diaspora. The old definition of diaspora only consisted of the dispersion of the Jews; however, 'diaspora', today, is known as the dispersal of people from their original homeland. Similar to ethnicity, the diaspora contains three unique features: dispersal, the concept of a homeland, and conscious group identity. Dispersal occurs when the people are traditionally forced to move out of their homeland into different locations. The concept of homeland is when the definition of 'home' divides into an 'actual' and an 'imagined' homeland. For instance, since Koryo Saram began in Primorsky krai, their actual homeland could be considered as Primorsky Krai; Some consider North Korea as their homeland, which is more of an imagined one.

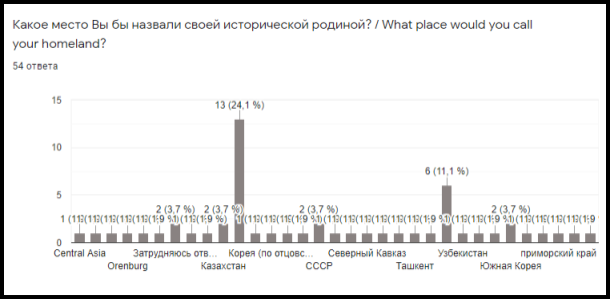

Fig. 2. Survey results, August 2020

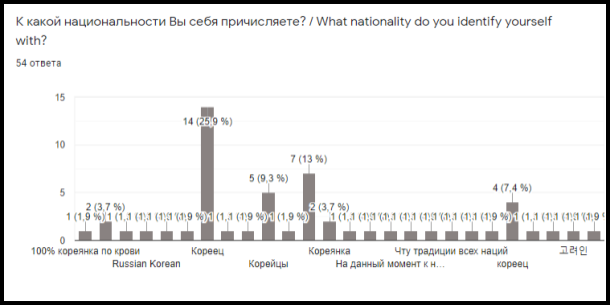

Lastly, the conscious group identity would be referred to as a certain ethnic group's unique characteristics. Although 31 of the respondents claimed that their nationality belongs to Korea, 2 claimed Koryo Saram, and 2 people claimed that they were Russian. However, the responses differed when we asked about their national homeland. 18 claimed that Korea was their national homeland, 4 claimed Kazakhstan, 9 claimed Uzbekistan, 4 claimed the former USSR, and 1 said that the United Korea (North and South) is their homeland.

Fig. 3. Survey results, August 2020

As shown, it is difficult to conclude a specific identity for the Koryo Saram as they are a diasporic group of people. This is because their ancestral homeland and history are founded in Korea. However, the title of «Koryo Saram» and their own unique identity developed right when they migrated to Primorsky krai. In short, their own true history began in Primorsky krai, but they are historically Korean. Aleksandr and many Koryo Saram believe that their nationality belongs to Korea, whereas their homeland is in Russia.

Korea, as well, being an imaginary home of most Koryo Saram, has gone through a significant ethical transformation within the acceptance of Koryo Saram. «Minjok» is a Korean word defined as 'one country, one people, and one language'; «Danil Minjok» is a Korean word defined as 'one blood'. Considering such conceptual factors, it was hard for such people 'without an identity' to fit in the idea of «minjok».

According to the Overseas Koreans Foundation Act (OKA) [4], to fall under the identity of 'overseas Korean' they must have a nationality «of the Republic of Korea, and stay in a foreign country for a long time or obtain permanent residency in a foreign country», and «regardless of their nationality» chooses to «reside and live in a foreign country». However, Koryo Saram did not fit in these categories either («Statutes of the Republic of Korea»).

Continuously, Koryo Saram were not accepted or given an identity that would truly define who they are. In 2004, they were recognized as foreign compatriots: ones who left Korea in 1948. In other words, they were considered more like Soviet citizens than Koreans.

A visa called F4 visa was created in 2004 and was applied for the Koryo Saram in 2010. This was one of the massive transformations, which accepted the identity of Soviet Koreans. With this visa, the Koryo Saram were allowed to work and live in their 'homeland', Korea.

However, there were multiple bitter aspects of the F4 visa: struggles within employment, shortage of visas, and restrictions from the 4th generation. Since the Koryo Saram were not accustomed to the Korean language, most jobs neglected them. The only jobs that were opened for them were called the '3D work', which are «dirty, dangerous, and difficult». In addition, the visa lasts for only about five years, which is extremely temporary. What's worse, the F4 visa is not provided to the 4th generation of the Koryo Saram. As if it was a cycle, the problem of identity occurred once again: the 4th generation started to face the difficulties that their ancestors did back in the former USSR.

Along with the issues of visa, discrimination took place within the Soviet Koreans. Sumin, a Koryo Saram who settled in Korea with the F4 visa, claims that she was « perceived as foreigners» and that « people stared at (her)" as if «something was on (her) face » [10]. Victoria, a Koryo Saram who was nearly fluent in Korean, was « happy to be in a homeland of (her) ancestors» ; however, she was treated « as a foreigner» if she « made a mistake or did not perform well enough». [10] As such, discrimination grew deeper amongst the Koryo Saram in Korea.

Not only within the ground of Korea, but Koryo Saram also faced discrimination from all around the world. Almost 80 %, which is a large number of people within the public survey, faced discrimination from a variety of countries, in which 60 % of them were due to their nationality. Some first hand experiences were due to their appearance. They were called ««Узкоглазая» (narrowed-eyes)», «Vегуки» (BTS V and Jungkook), «nerus» (non-russian), and so on. Some were not even allowed to go in the karaoke club simply because «(they) were veggies.» What’s worse, one surveyor’s grandmother «called (him) a nerus, and the rest of the people either grinned or pretended not to hear his cry.» Despite all this discrimination, 78.8 % of the surveyors still stated that they were Koreans and 59.9 % of them defined themselves as Koryo Saram [10].

Looking at Russia's perspectives, Primorsky Krai was presented as land for those Koreans, including Koryo Saram, Chinese Koreans, and North Koreans. In 1989, the Soviet Communist Party's Committee adopted the resolution called, «Concerning the Problem of Nationalities «at present, which did recognize the deported Koreans. Through this resolution, a «friendship village» was created, which was idealized to experiment with how the Korean Peninsula might act or behave after the unification. However, the experiment reached a huge failure. Many South Korean entrepreneurs disliked working with Koryo Saram since they did not work as hard as modern Korean or Russians. Although, in history Koryo Saram was seen as one of the most hardworking people, as of now, not only do they not have many opportunities, but there are also countless Koreans and Russians working hard to pursue their aims in life.

Nevertheless, Primorsky Krai and the Russian government recognized the necessity of spreading awareness of the Koryo Sarams' history. This is because they would like to offer help to recover Koryo Sarams' national identity and avoid repetition of the past. Thus, in 1993, Primorsky Krai Fund for Korean Revival was established to legally and financially support the Soviet Koreans. Similarly, the Association for National and Cultural Autonomy of Russia helped Koryo Saram find and adapt to their own cultural aspects.

As shown, both Korea and Russia seem to have a similar perception towards Koryo Saram. As it is difficult to accept them as their citizens, they are willing to help them only up to a certain extent. Therefore, some take it as a type of discrimination and mistreatment. However, most Koryo Saram like Aleksandr «have never thought of any unfair treatment from the government because it is (their) duty to serve (their) country». In fact, they do not bring up such unpleasant events of their history; Aleksandr found out such horrific histories such as the deportation «through the television in the 1990s» since «no one in the family ever spoke about it». [9].

Koryo Sarams’ history is not something that they are hiding or ashamed about, but rather a long period of time that they had to go through to gain the certainty of where they can call ‘home’. Koryo Saram are the patient ones whom are waiting to settle in an identity, where in spring, the seeds will sprout; in summer, their flowers will bloom; in fall, their leaves will fall, and in winter, the snowflakes will pile them up: that one place called home.

References:

- Cohen, Robin. Solid, Ductile and Liquid: Changing Notions of Homeland and Home in Diaspora Studies. 2007.

- Jo, Mi-Jeong. «Koryo Saram in South Korea: ‘Korean’ but Struggling to Fit in | KOREA EXPOSÉ.» KOREA EXPOSÉ, 29 May 2018, www.koreaexpose.com/koryo-saram-from-central-asia-and-russia-struggle-in-south-korea/. Accessed 18 Oct. 2020.

- Kim, German. «German Kim and Ross King. Koryo Saram: Koreans in the Former USSR. 2001, 180 p. Pdf.» Academia.Edu, 2020, www.academia.edu/37609382/German_Kim_and_Ross_King_Koryo_Saram_Koreans_in_the_Former_USSR_2001_180_p_pdf. Accessed 18 Oct. 2020.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Korea. «Overseas Koreans FoundationMinistry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Korea». 외교부. Accessed November 3, 2020. https://www.mofa.go.kr/eng/wpge/m_5722/contents.do

- «Statutes of the Republic of Korea» Klri.Re.Kr , 2010, elaw.klri.re.kr/eng_mobile/ganadaDetail.do?hseq=35126&type=abc&key=OVERSEAS %20KOREANS %20FOUNDATION %20ACT¶m=O. Accessed 18 Oct. 2020.

- «Как коресарам превратились в кореинов». KOREANS.KZ. Accessed August 5, 2020. https://koreans.kz/news/kak-koresaram-prevratilis-v-koreinov.html

- «Корейская деревня, как это было — Cтатьи — Каталог статей — с. Михайловка Михайловский район Приморский край». с. Михайловка Михайловский район Приморский край — Главная страница. Accessed August 5, 2020. https://mikhailovka.my1.ru/publ/korejskaja_derevnja_kak_ehto_bylo/1–1–0–5

- «ОБ ЭТОМ ГОВОРЯТ — Точка, точка… запятая?» Российские корейцы. Last modified June 29, 2020. https://gazeta.korean.net/index.php?document_srl=107140&mid=column

- An Interview with Aleksandr Leonidovich Ten. Recorded August, 2020

- Survey results, August 2020