Teachers use a communicative approach in language development to improve students' communication skills, as the most important thing is that students speak fluently. The purpose of the article is to theoretically substantiate the effectiveness of the test of communicative competence using oral testing, practical development and experimental testing, and the subject of the study is the test of communicative competence using oral testing.

In the study, the authors revealed the structure, content, criteria, indicators and levels of communicative competencies, identified the theoretical foundations of communicative competence and the principles of assessment of communicative competence.

Преподаватели используют коммуникативный подход к развитию языка для улучшения коммуникативных навыков учащихся, так как самое главное, чтобы учащиеся свободно говорили. Целью статьи является теоретическое обоснование эффективности проверки коммуникативной компетентности с помощью устного тестирования, практической отработки и экспериментальной проверки, а предметом исследования является проверка коммуникативной компетентности с помощью устного тестирования.

В ходе исследования авторы раскрыли структуру, содержание, критерии, показатели и уровни коммуникативных компетенций, выявили теоретические основы коммуникативной компетентности и принципы оценки коммуникативной компетентности.

Recent theoretical and empirical research on communicative competence is largely based on three models of communicative competence: the model of Canale and Swain, the model of Bachman and Palmer and the description of components of communicative language competence in the Common European Framework (CEF). The theoretical framework/model which was proposed by Canale and Swain (1980, 1981) had at first three main components, i.e. fields of knowledge and skills: grammatical, sociolinguistic and strategic competence. In a later version of this model, Canale (1983, 1984) transferred some elements from sociolinguistic competence into the fourth component which he named discourse competence. In Canale and Swain (1980, 1981), grammatical competence is mainly defined in terms of Chomsky’s linguistic competence, which is why some theoreticians (e.g. Savignon, 1983), whose theoretical and/or empirical work on communicative competence was largely based on the model of Canale and Swain, use the term «linguistic competence» for «grammatical competence». According to Canale and Swain, grammatical competence is concerned with mastery of the linguistic code (verbal or non-verbal) which includes vocabulary knowledge as well as knowledge of morphological, syntactic, semantic, phonetic and orthographic rules. This competence enables the speaker to use knowledge and skills needed for understanding and expressing the literal meaning of utterances. In line with Hymes’s belief about the appropriateness of language use in a variety of social situations, the sociolinguistic competence in their model includes knowledge of rules and conventions which underlie the appropriate comprehension and language use in different sociolinguistic and sociocultural contexts [1].

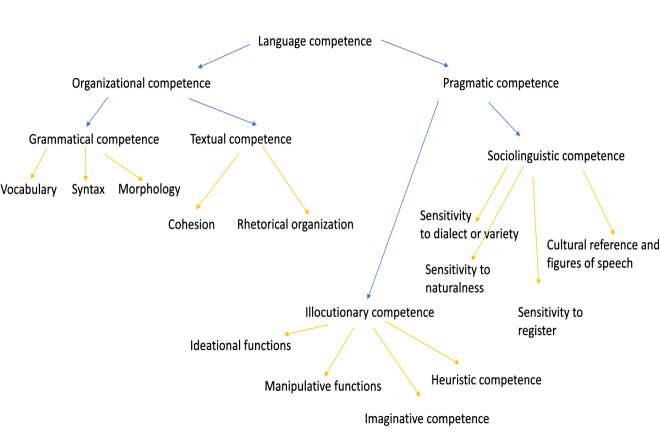

Lyle Bachman distinguishes an organizational competence which consists of grammatical (vocabulary, morphology, syntax, phonology and graphology) and textual competences (cohesion, rhetorical organization).

Organizational competence, he says, is that part of language ability which enables speakers to use grammatically correct sentences, either in isolation or in larger chunks of text, and accurately convey propositional content. In short, it is the database of vocabulary and grammatical rules students garner during their studies. Bachman also includes textual competence in this category, namely cohesion and rhetorical organization, which encompasses the knowledge of conventions for joining utterances together [2, p.87].

Bachman, concerned mainly with language testing, asked himself a question whether strategic competence (dealt with in greater detail below) is relevant to language abilities assessment. He answers this question by maintaining that strategic competence is not to be considered solely as a language ability, but as a general ability to carry out a task effectively. He provides an example of two candidates dealing with a test task focusing on the practical outcome. While one examinee might be preoccupied with constructing grammatically flawless sentences and using a wide range of vocabulary, the other might be more goaloriented and at the expense of making grammatical mistakes efficiently works his/her way toward task completion. As the task was effective communication, the latter examinee was awarded higher marks than the former [2, p.104]. It was clear to Bachman that testing the knowledge merely of linguistic signals would not suffice if one desired to carry out a thorough language abilities assessment. He maintains that language communication inherently consists of the relationships between linguistic signals and their referents, language users and context. Consequently, he labeled these abilities the pragmatic competence.

Fig. 1. Bachman’s components of language competence

Considering illocutionary competence, there are many strategies to perform an illocutionary act. Bachman introduces an example of asking someone for help differing in the amount of subtlety or directness used [2, p.91]. A native or proficient speaker naturally distinguishes and is capable of applying such strategies, e.g. selecting an appropriate text from the following:

a) I request that you help me.

b) Please help me.

c) If you help me, I’ll buy you a new comic book.

d) Could you help me?

e) Why aren’t you helping me?

The obligatory lexical items we are dealing with here are:

I/you/me,/help/request//buy/to be/could/why/if/will/please all of which an A2 student customarily knows. Yet I believe that not many students would be able to construct so many possibilities to execute the aforementioned illocutionary competence.

An interesting part of Bachman’s theory of communicative language use is his Model of language use. He elaborates on the steps of language execution with respect to utilizing organizational competence, taking into consideration context and strategic competence. The first step is the goal which is to interpret or express speech with a specific function, modality, and content [2, p.103]. Bachman proceeds through three subsequent steps to arrive at utterance, i.e. expressing or interpreting language.

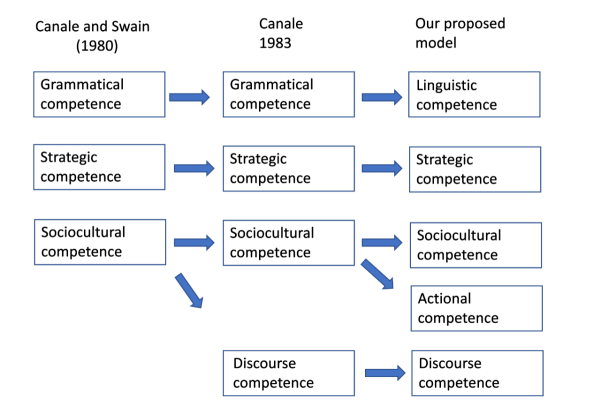

Figure 3. Chronological evolution of the proposed model

Figure 2 shows chronological evolution of the proposed model. In 1983 Canale divided discourse competence from the sociocultural competence and then specifies new actional competence. Canale and Swain (1980) started to narrow sociolinguistic dimension by separating strategic competence from sociolinguistic competence. Main distinction between our model and Canale and Swain’s is that we use the term «linguistic competence» rather than «grammatical competence» in order to indicate that this component also includes lexis and phonology in addition to morphology and syntax.

Linguistic competence (also referred to as «grammatical competence») is historically the most thoroughly discussed component of our CLT model and, for this reason, our present description of it will be brief. It comprises the nuts and bolts of communication: the sentence patterns and types, the constituent structure, the morphological inflections, and the vocabulary as well as the phonological and orthographic systems needed to realize communication as speech and writing.

In the past linguistic competence has often been the primary goal of foreign language teaching [3]. This position is obviously untenable. However, in their zeal to give social and notional-functional aspects oflanguage proper consideration in CLT, many CLT proponents neglected linguistic competence and accepted the premise that linguistic form emerges on its own as a result of learners' engaging in communicative activities [4].

General agreement is now emerging on the fact that applied linguistics needs a new approach to CLT which recognizes that linguistic competence does not emerge on its own, and which fully integrates linguistic competence with the other competencies. This amounts to acknowledging that linguistic resources are a necessary instructional objective in any interactional method. To accomplish this, language teachers and materials developers must have explicit training in the linguistic system of the target language. For background in syntax and morphology in English, see CelceMurcia and Larsen-Freeman (1983); for background in phonology and orthography, see Celce-Murcia, Brinton, and Goodwin (in press). Teachers also need guidance on how to integrate the linguistic system of the language they are teaching with the other components of our expanded CLT model and how to translate this knowledge into pedagogical activities that will benefit their students.

The final point we would like to make about linguistic competence concerns the interrelated nature of grammar and lexis mentioned above. In language teaching practice this interplay has been recognized by introducing the term «usage», and indeed we find many examples of «lexicalized sentence stems» [5] or «formulaic constructions» [6] in most languages, where grammatical formulae are paired with some fixed lexical content.

Discourse competence concerns the selection, sequence, and arrangement of words, structures, and utterances to achieve a unified genre-sensitive spoken or written text. There are many sub-areas that contribute to this competence: cohesion, deixis, coherence, generic structure, and the conversational structure inherent to the turn-taking system in conversation.

Cohesion is the area of discourse competence most closely associated with linguistic/grammatical competence. It deals with the bottom-up elements that help generate text. This area accounts for how pronouns, demonstratives, articles and other markers signal textual co-reference in written and oral discourse. Cohesion also accounts for how conventions of substitution and ellipsis allow speakers/writers to avoid unnecessary repetition. The use of conjunction (e.g., and, but, however) to make explicit links between propositions in discourse is another important cohesive device. Lexical chains and lexical repetitions, which relate to derivational morphology, semantics, and content schemata, are a part of cohesion and also coherence, which we discuss below. Finally, the conventions related to the use of parallel structure, which are also an aspect of both cohesion and coherence, make it easier for listeners/readers to process a sentence such as «I like swimming and hiking» than to process an unparallel counterpart such as «I like swimming and to hike». The deixis system is an important aspect of discourse competence in that it links the situational context with the discourse, thus making it possible to interpret deictic personal pronouns (I, you); spatial references (here, there); temporal references (now, then); and certain textual references (e.g., the following example). Deixis also is related to sociolinguistic competence; for example, in the choice of vous/tu in French or Sie/du in German, or the choice of modal verbs in requests for permission in English (May 1...? vs. Can 1...?). The most difficult area of discourse competence to describe is coherence, and it is typically easier to describe coherence in written than in oral discourse. There is some overlap with cohesion, as we have mentioned above, but coherence is more concerned with macrostructure in that its major focus is the expression of content and top-down organization of propositions. Coherence is concerned with what is thematic (i.e., what is the point of departure of a speaker/writer's message).lt is concerned with the management of information in a system where old information generally precedes new information in propositions. Also part of coherence is the sequencing or ordering of propositional structures, which generally follows certain preferred organizational patterns: temporal/chronological ordering, spatial organization, cause-effect, condition-result, etc. Temporal sequencing has its own conventions in that violations of chronological order must be marked using special adverbial signals and/or marked tenses.

Topic continuity and topic shifts are aspects of discourse coherence that have been studied most carefully within the narrative genre [7]. Here again cohesive devices such as reference markers, substitution/ellipsis, and lexical repetition are used to establish coherence. Closely related to topic continuity and shift is the phenomenon of temporal continuity and shift (or sequence of tenses) already alluded to above in our mentioning of the temporal sequencing of propositions.

Languages often have special framing devices that exploit the tense-aspect-modality system to allow speakers/ writers to indicate that stretches of text cohere [8]. For example, in English an episode with «used to» in its opening proposition followed by a sequence of «would/' d«tokens in subsequent propositions is typical of narrative dealing with the habitual past. Similarly, an episode with «be going to» in the opening proposition followed by «will/,ll» in subsequent propositions is typical of future scenarios. The generic structure of various types of spoken and written texts has long been an object of concern in discourse analysis [9]. Every language has its formal schemata, which relate to the development of a variety of genres. Certain written genres have a more highly definable structure than others, e.g., research reports (introduction, methods, results, discussion). Likewise, certain spoken genres such as the sermon tend to be more highly structured than oral or written narrative, which is a more open-ended genre but with a set of expected features nonetheless (opening/setting, complication, resolution-all within a unified framework regarding time and participants).

The final aspect of discourse competence that we have outlined above is conversational structure, which is inherent to the tum-taking system in oral conversation [10]. This area is highly relevant for CLT, since conversation is the most fundamental means of conducting human affairs. While usually associated with conversation, it is important to realize that these tum-taking conventions may also extend to other oral genres such as narratives, interviews, or lectures. The tum-taking system deals with how people open and reopen conversation, how they establish and change topics, how they hold and relinquish the floor, how they backchannel, how they interrupt, hav they collaborate, and ha.v they perform preclosings and closings. These «interactive procedures» are often performed by means of «discourse regulating gambits» [11] or conventionalized formulaic devices, which take the form of phrases or conversational routines. Polished conversationalists are in command of hundreds, if not thousands, of such phrases, and these phrases lend themselves to explicit classroom teaching.

The turn-taking system is closely associated with the notion of adjacency pairs and also with repair, i.e., how speakers correct themselves or others in conversation, which we discuss under strategic competence. Adjacency pairs form discourse «chunks» where one speaker initiates (e.g., Hi, how are you?) and the other responds (e.g., Fine, thanks. And you?) in ways that are describable and often quite predictable. Some adjacency pairs involve giving a «preferred» response to a first-pair part (e.g., in accepting an invitation that has just been extended); such responses are usually direct and structurally simple. However, other responses are viewed as «dispreferred» and will require more effort and follow-up work on the part of participants than will a preferred response (e.g., when declining an invitation). Dispreferred responses occur less frequently than the preferred ones, and tend to pose more language difficulties for learners. To conclude this section, we would like to emphasize once again that discourse forms the crucial central component in our model of communicative competence. This is where the nuts and bolts of the lexico-grammatical microlevel intersect with the top-down signals of the macro level of communicative intent and sociocultural context to express attitudes and messages, and to create texts [12].

Actional competence can be described as the ability to perform speech acts and language functions, to recognize and interpret utterances as (direct or indirect) speech acts and language functions, and to react to such utterances appropriately. While we are critical of the «functions only» approach to CLT and, indeed, there are some indications that speech act theory is gradually losing favor in pragmatics and applied linguistics [13], we believe that actional competence is an important part of L2 interactional knowledge. The frequency with which language functions are used has resulted in highly conventionalized forms, fixed phrases, routines and strategies in every language. Learners need to build up a repertoire of such phrases to be able to perform speech acts effectively, and therefore we must assign them an important place in interactional syllabuses. The system of language functions has traditionally been the most highly developed linguistic content area in CLT. In the 1960's and 1970's Austin (1962) and Searle's (1969) speech act theory and Halliday's (1973) work on functional systems prepared the ground for a new approach to defining language teaching syllabuses based on perfonnance objectives, that is, stressing the importance of what people do with language over linguistic fonn. In the mid-70's Wilkins (1976) introduced the concept of a functional syllabus, and van Ek (1977) in his Threshold Level, produced a detailed and practical set of language functions to serve as a workable guide for classroom teachers and materials writers.

Sociolinguistic competence refers to the speaker's knowledge of how to express the message appropriately within the overall context of communication; in other words, this dimension of communicative competence is concerned with pragmatic factors related to variation in interlanguage use. These factors are complex and interrelated, which stems from the fact that language is not simply a communication coding system but also an integral part of the individuals' identity and the most important channel of social organization, embedded in the culture of the communities where it is used. As Nunan [14] states, «Only by studying language in its social and cultural contexts, will we come to appreciate the apparent paradox of language acquisition: that it is at once a deeply personal and yet highly social process». Language learners face this complexity as soon as they first try to apply the L2 knowledge they have learned to real-life communication, and these first attempts can be disastrous: the «culture-free», «out of-context» and very often even «meaning-free» L2 instruction [15] which is so typical of foreign language classes around the world, simply does not prepare learners to cope with the complexity of real-life language use efficiently. L2 learners should be made aware of the fact that making a social or cultural blunder is likely to lead to far more serious communication breakdowns than a linguistic error or the lack of a particular word. Raising sociolinguistic awareness, however, is not an easy task, because, as Wolfson [16. 9,215] points out, sociolinguistic rules and normative patterns of expected or acceptable behavior have not yet been adequately analysed and described. She does, however, argue that «language learners and others who are involved in intercultural communication can at least be made sensitive to the fact that these patterns exist, and can be guided in ways to minimize misunderstandings».

Strategic competence can be conceptualized as the knowledge of and competence in using communication strategies. Definitions of communication strategies typically highlight three functions of strategy use:

(a) Overcoming problems in realizing verbal plans, e.g., avoiding trouble spots or compensating for not knowing a vocabulary item.

(b) Sorting out confusion and partial or complete misunderstanding in communication, e.g., by employing repair or negotiating meaning [16. p,308].

(c) Remaining in the conversation and keeping it going in the face of communication difficulties, and playing for time to think, e.g., by using gambits, fillers or hesitation devices.

References:

- Семенова И. М. COMMUNICATIVE COMPETENCE. М.: ИКАР. — 2009. — 225 c.

- Bachman L. F. et al. Fundamental considerations in language testing. — Oxford university press, 1990. — P. 378.

- Rutherford W. E. Second language grammar: Learning and teaching. — Routledge, 2014. — 252 p.

- Krashen S. D. The input hypothesis: Issues and implications. — Addison-Wesley Longman Limited, 1985. — 186 p.

- Pawley A., Syder F. H. Two puzzles for linguistic theory: Nativelike selection and nativelike fluency //Language and communication. — 1983. — Т. 191. — 225 p.

- Pawley A. Formulaic speech //International encyclopedia of linguistics. — 1992. — Т. 2. — 22–25 pp.

- Givón T. Topic continuity in discourse: A quantitative cross-language study. — John Benjamins Publishing, 1983. — Т. 3. — 86 p.

- Suh K. H. A discourse analysis of the English tense-aspect-modality system: дис. — University of California, Los Angeles, 1992. — 95 p.

- Swales J. Genre analysis: English in academic and research settings. — Cambridge University Press, 1990. — 247 p.

- Schegloff E., Jefferson G., Sacks H. A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation //Language. — 1974. — Т. 50. — №. 4. — 696–735 pp.

- Kasper G. Interactive procedures in interlanguage discourse //Contrastive pragmatics. — 1989. — Т. 3. — 189–230 pp.

- Celce-Murcia M., Dörnyei Z., Thurrell S. A pedagogical framework for communicative competence: content specifications and guidelines for communicative language teaching //Deseret language and linguistic society symposium. — 1993. — Т. 19. — №. 1. — 3 p.

- Levinson S. C. Pragmatics and the grammar of anaphora: A partial pragmatic reduction of binding and control phenomena //Journal of linguistics. — 1987. — Т. 23. — №. 2. — 434 p.

- Nunan D. Sociocultural aspects of second language acquisition //Cross Currents. — 1992. — 65 p.

- Damen L. Culture learning: The fifth dimension in the language classroom Reading //MA: Addison-Wesley. — 1987. — 216 p.

- Wolfson N. Perspectives: sociolinguistics and TESOL. — Newbury House Publishers, 1989. — P. 336.