The Helmand River is the longest river in Afghanistan and the most important source of water for irrigation in the country. The river is facing numerous challenges due to climate change, including reduced water availability, changes in precipitation patterns, and increased temperatures. These impacts are expected to worsen in the coming years, and could have serious consequences for the people and ecosystems that depend on the river. This review article examines the available literature on the impact of climate change on the Helmand River, and discusses the potential implications for water resources management in the region. The purpose of this review article is to provide a comprehensive overview of the impact of climate change on the Helmand River, including its water resources, ecosystem, and agriculture.

Keywords: Helmand River, Climate change, Water availability, Ecosystem, Water resources management.

1. Introduction

Changes in the hydrological regime are mostly caused by global warming and human activities. The hydrological system is very susceptible to climatic fluctuations, especially precipitation and temperature. The global hydrological cycle has already been altered by recent climate change. These effects have expressed themselves in altered seasonal river flows and an increase in the frequency and intensity of floods and droughts in some places (Gnjato et al. 2019). In addition, Global warming refers to the rapid increase in the average surface temperature of the Earth over the past century, which is primarily driven by greenhouse gases emitted when people burn fossil fuels. The average worldwide surface temperature rose by 0.6 to 0.9 degrees Celsius (1.1 to 1.6 degrees Fahrenheit) between 1906 and 2005, and the rate of temperature increase has nearly doubled in the last 50 years (“Global Warming” 2010). In this cause, increases in land surface temperature will have a considerable impact on the hydrological cycle, especially in locations where snow or ice melting is the dominant source of accessible water. In cold and mountainous places, the hydrological cycle will be severely affected by the removal of permafrost layers, glacial recessions, and variations in snowmelt (Aung, Fischer, and Azmi 2020).

The distribution of precipitation is essential for water management, particularly in dry and semiarid countries. Estimating precipitation quantitatively is essential for comprehending the hydrological balance and improving climate forecast models. Recent climatological models predict that due to global warming, the East Mediterranean/Middle East will experience less precipitation and a lower river discharge (Yatagai, Xie, and Alpert 2008). Understanding how climate change affects annual and seasonal discharge and the difference between median flow and extreme flow in different climate regions is very important for water management (Xu and Luo 2015).

Afghanistan, a landlocked nation, has 652000 square kilometers. About 82 % of Afghanistan's total land is rangeland and bare land, less than 2 % is covered by forests, and approximately 10 % of the terrain is arable. One-fourth of Afghanistan's landmass stands above 2,500 meters above sea level. In Afghanistan, precipitation and snowfall are the primary sources of river flow. Afghanistan's river basins have their origins in the high altitudes of the Pamir and Hindukush mountain ranges (Goes et al. 2016). Afghanistan's water flow is divided into five river basins:

- The Amu Darya river basin

- The Helmand river basin

- The Kabul (Indus) river basin

- The Harirod -Morghab river basin.

- The Northern river basin.

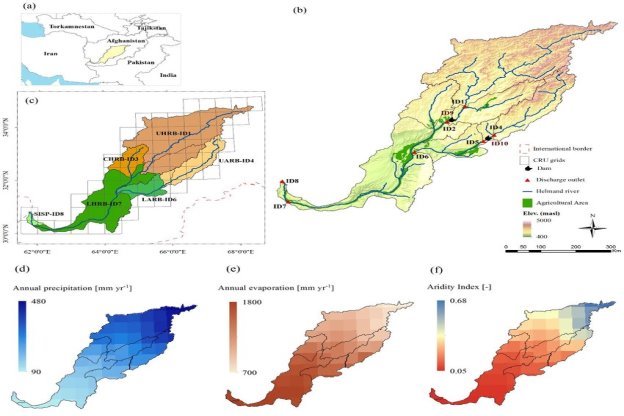

The Government of Afghanistan has split irrigation water into four classifications based on its source: rivers and streams, 84.6 % springs, 7.9 % karezes (kanats), 7 % shallow and deep wells, and 0.5 % other. The majority of Afghanistan's water supply, including water for drinking (potable water), irrigation, and the maintenance of wetland ecosystems (surface and ground water), is derived from precipitation falling within Afghanistan's borders and the seasonal melting of snow and glaciers in the country's highlands. Unfortunately, Afghanistan has been unable to fully use its water potential. In the absence of a comprehensive water strategy plan, Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) is a significant issue that the Afghan government must address (Bekturganov et al. 2016). The Helmand river basin, as illustrated in Figure 1, is a restricted river basin that discharges into a sequence of terminal lakes, commonly referred to as hamouns, situated in the Sistan Depression in proximity to the border between Afghanistan and Iran. The basin is estimated to have a collective area of roughly 400,000 square kilometers and is geographically dispersed across southern Afghanistan (81.4 % of the basin), Iran (15 %), and Pakistan (3.6 %). The elevations of the basin vary from approximately 4400 meters above sea level (masl) in the northeastern Hindu Kush Mountains, which serve as the primary source of the basin's rivers, to 490 masl in the southwestern Sistan depression (Goes et al. 2016). The purpose of this review article is to provide a comprehensive overview of the Impact of climate change on the Helmand River, including its water resources, ecosystem, and agriculture. The review will examine the available literature on climate change and its impact on the Helmand River Basin and highlight current and future adaptation measures.

Fig. 1 (a) The location of the Helmand River Basin (HRB) in central Afghanistan, (b) an elevation map of the HRB that also shows the boundaries of the sub-basins, where the sub-basin outlets are located, and the area that is currently used for agriculture (as (as of 2006), (c) an outline of the sub-basins, (d) long-term mean annual precipitation P [mm y -1], (e) long-term mean annual potential evaporation EP

Sources: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/a-The-location-of-Helmand-River-Basin-HRB-in-central-Afghanistan-b-elevation-map_fig1_343191809

2. Water Quality:

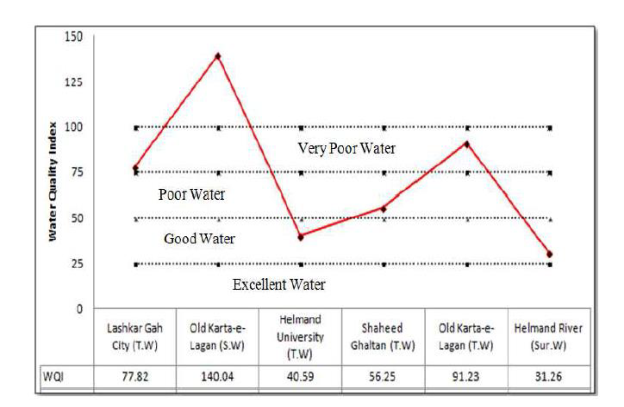

The Helmand River's extremely low level of total dissolved solids is an essential characteristic. The main factor preventing salts from concentrating significantly in the hamuns is presumably the cleanliness of the water. The hamuns typically range in depth from 1.5 to 3.0 meters, and after another 1.5 meters of depth, they will overflow into the Gaudi Zirreh. However, some salt concentration is anticipated if the extremely high evaporation rates on the delta area are accurate. The fact that certain alkaline salts are absorbed into the groundwater is one explanation for the comparatively fresh water. As an alternative, some researchers think that the salts dissolve at times of strong flow, are flushed into the Gaudi Zirreh, and are subsequently expelled from the basin when the hamun is dry. The hydrology records of the Helmand River show that the individual hamuns dramatically diminish, or totally dry out, once or twice a decade, which is more frequently than previously described, suggesting that salt deflation probably occurs more frequently. Another hypothesis is that during floods, a significant amount of sediment is deposited, quickly burying salt. In any case, the Sistan hamuns continue to be Southwest Asia's only free-standing, relatively freshwater bodies of water that are not man-made or situated in mountainous terrain (USGS 2006). Regarding Groundwater quality Water samples collected from various locations, including GW of Lashkar Gah city, Helmand University, Shaheed Ghaltan, and Old Karta-e-Lagan, exhibit alkaline properties, as evidenced by their respective pH values of 7.95, 8.25, 8.07, and 8.16. The hydrological characteristics of a water body may be contingent upon the geological composition of the surrounding rocks, such as those comprised of limestone. The investigation discloses that the electrical conductivity (EC) of water samples collected from the Old Karta-e-Lagan district, specifically from SW and TW, are measured to be 4700 and 3250 μS/cm, respectively. These values surpass the allowable threshold. This phenomenon could potentially be attributed to the existence of soluble minerals within the underlying bedrock. The water salinity levels at three distinct locations, namely a SW and TW in Old Karta-e-Lagan district and a TW in Lashkar Gah city, were measured to be 2510, 1690, and 1280 mg/L, respectively. These values surpass the acceptable threshold of 1000 mg/L as stipulated by the World Health Organization in 2008. The ingestion of water with a high salinity concentration has been linked to adverse health effects such as joint pain, skin allergies, gastrointestinal upset, vomiting, and diarrhea. The TDS measurements of two locations situated in the Old Karta-e-Lagan district have been determined to be 2780 and 1623 mg/L, respectively. These values exceed the acceptable threshold of 1500 mg/L as stipulated by the World Health Organization in 1963 (fig. 1) (Ansari et al. 2021).

Fig. 2 Values of Groundwater Water Quality Index for all studied samples. Source: (Ansari et al. 2021)

3. Ecosystems:

The freshwater ecosystems consist of extensive wetlands or swamps that encompass open freshwater bodies, such as lakes, as well as reed beds or neizar, and the rivers that supply water to the lakes. The wetlands serve as a significant source of freshwater amidst vast expanses of dry grasslands spanning hundreds of kilometers. Freshwater is only available in a limited number of isolated springs. The basin's freshness is maintained through overflow to the Gaud-e Zirreh, a salt flat, which provides a flushing effect and prevents the accumulation of salts, distinguishing it from other terminal sumps. The size of the marshes and lakes is significantly influenced by the flood patterns of the Helmand River, which exhibit natural fluctuations resulting in occasional desiccation of the lakes. Consequently, fish populations recolonize these water bodies from the river (“Xeric Freshwaters and Endorheic (Closed) Basins” n.d.). Moreover Approximately 40 % of the species within the ecoregion exhibit endemism, with four of them belonging to the Paracobitis genera (namely, P. boutanensis, P. ghazniensis, P. rhadinaeus, and P. vignai). The absence of endemic genera is notable, however, the Sistan lakes are home to the Schizothorax zarudnyi (Cyprinidae) snow trout, which is a species that is exclusive to this region. Additional endemic species found in the region comprise Schizocypris altidorsalis located in Sistan, Nemacheilus kullmanni inhabiting the Ab-e-Nawar spring, and Schistura alta and Triplophysa farwelli present in the Helmand River drainage (“Xeric Freshwaters and Endorheic (Closed) Basins” n.d.).

4. Agriculture

Agriculture is the primary source of livelihood for people living along the Helmand River. However, agriculture has also had a significant impact on the river, including increased water consumption, the use of fertilizers and pesticides, and the conversion of natural vegetation into farmland (FAO. 2016). These activities have led to soil erosion, reduced soil fertility, and contamination of the river water, leading to a decline in agricultural productivity and the degradation of the river ecosystem.

Furthermore Helmand The pre-war and current economy is predominantly reliant on agriculture, accounting for 75–80 % of the economy, followed by livestock at 15–20 %, and services at 5 %. The manufacturing industry lacks significant presence. As previously stated, Helmand was once considered a region with significant agricultural potential. As a result, prior to the 1970s, various governments placed considerable emphasis on maximizing the utilization of this available potential. The crops that are commonly grown in the region include wheat, mungbeans, beans, maize, a variety of vegetables, onions, melons and watermelons, cotton, tobacco, and sugar beet (“European Country of Origin Information Network — Ecoi.Net” n.d.).

Conversely, subsequent to the establishment of Kajaki Dam, the governing body of that era executed an agricultural initiative in Helmand, which entailed the construction of three canals. The objective of the project was to establish Helmand as a hub for the production and dissemination of high-quality seeds, including cereals and vegetables, with a specific focus on onion seeds, for global consumption. Agricultural experts confirmed that all essential investigations pertaining to soil, climate, water, and experimentation had been conducted (“European Country of Origin Information Network — Ecoi.Net” n.d.).

5. Population Growth and Urbanization

As of 2018, the most recent recorded population figure stands at approximately 956,000. 2.736 % of the entire population of Afghanistan constituted the aforementioned figure. The population density of Helmand was recorded as 16.4 individuals per square kilometer. Assuming a consistent population growth rate of 1.51 % per year, the projected population of Helmand in 2023 would be 1,030,153. This estimation is based on the population growth rate observed during the period of 2006–2018 (“Helmand Population” n.d.).

Population growth including urbanization have led to increased demand for water, leading to increased water consumption and the development of water-intensive industries. Moreover, population growth has also led to the conversion of natural vegetation into urban areas, leading to the loss of natural habitats and the degradation of the river ecosystem. Moreover, the increase in population has also led to the generation of more waste, leading to increased pollution and degradation of the river water quality.

6. Water Resources Management:

The management of the Afghan portion of the basin is undergoing a transition from being based on provincial demarcations to being based on hydrological demarcations. The establishment of the Helmand River Basin Agency (HRBA) and nine Sub-basin Agencies (SBAs) in 2012 is a clear indication of the transition that has taken place, which was brought about by the enactment of the Afghan Water Law in 2009. The majority of water projects that received international support between 2004 and 2010 had a military perspective, with an emphasis on enhancing security and promoting stabilization. Since 2010, the emphasis of water projects that receive international support has shifted towards development, with a focus on enhancing institutional capacity and strengthening the SBAs (Goes et al. 2016). Additionally, these projects aim to support the enhancement of formal irrigation systems. The primary canal and head regulator of the Dahla Irrigation Project underwent noteworthy enhancements between 2008 and 2011, with support from Canada. Limited efforts have been made in Helmand province to fortify canal regulators against scour damage, while comparatively less attention has been devoted to the restoration of control gates, which pose greater challenges in terms of rehabilitation (Goes et al. 2016).

To address these challenges, water resources management in the Helmand River basin will need to be adaptive and resilient to the impacts of climate change. This will require a range of interventions, including improvements in water use efficiency, the development of new water sources, and the implementation of sustainable land use practices. In addition, effective water governance mechanisms will be essential to ensure equitable and sustainable allocation of water resources.

7. Conclusion:

The Helmand River is facing significant challenges due to climate change, including declining water quality, and ecosystem degradation. These impacts are already being felt in the region, and are expected to worsen in the coming years. The implications of these impacts for water resources management in the region are significant, and will require a range of adaptive and resilient interventions to ensure the sustainable management of water resources in the Helmand River basin. Failure to address these challenges could have serious consequences for the people and ecosystems that depend on the river, and could exacerbate existing economic and social vulnerabilities in the region.

The following measures could be implemented:

- Improve water use efficiency: The agricultural sector is the main user of water in the Helmand River basin. It is, therefore, crucial to improve water use efficiency to reduce water consumption while maintaining or improving crop productivity. Measures such as drip irrigation, laser leveling, and crop rotation could be implemented to reduce water consumption in agriculture.

- Develop new water sources: Developing new water sources could help increase water availability in the basin. Measures such as rainwater harvesting, wastewater reuse, and desalination could be implemented to augment water supplies.

- Implement sustainable land use practices: Unsustainable land use practices such as deforestation and overgrazing have contributed to the degradation of the Helmand River’s ecosystems. The implementation of sustainable land use practices such as afforestation, reforestation, and sustainable grazing could help restore the river’s ecosystems.

- Strengthen water governance: Effective water governance mechanisms are essential to ensure equitable and sustainable allocation of water resources in the Helmand River basin. The establishment of effective water governance mechanisms such as river basin organizations, stakeholder participation, and water pricing could help ensure sustainable management of water resources in the basin.

- Reduce greenhouse gas emissions: Reducing greenhouse gas emissions is crucial to mitigate the impacts of climate change on the Helmand River. Measures such as renewable energy development, energy efficiency improvements, and transportation reforms could be implemented to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

8. Recommendations for future research

Future research should focus on the development and implementation of effective climate change adaptation and mitigation strategies in the Helmand River Basin. This includes research on the effectiveness of current adaptive measures, the development of climate-resilient crops and irrigation systems, and the conservation and restoration of wetlands and habitats.

References:

- Ansari, Ahmad, Alper Baba, Muhammad Mukhlisin, and Sivarama Krishna. 2021. “Water Quality Assessment of Ground and River Water in Lashkar Gah City of Helmand Province, Afghanistan.” International Journal of Pharmaceutical Research 13 (01). https://doi.org/10.31838/ijpr/2021.13.01.313.

- Aung, Thiri Shwesin, Thomas B. Fischer, and Azlin Suhaida Azmi. 2020. “Are Large-Scale Dams Environmentally Detrimental? Life-Cycle Environmental Consequences of Mega-Hydropower Plants in Myanmar.” The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 25 (9): 1749–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367–020–01795–9.

- Bekturganov, Zakir, Kamshat Tussupova, Ronny Berndtsson, Nagima Sharapatova, Kapar Aryngazin, and Maral Zhanasova. 2016. “Water Related Health Problems in Central Asia—A Review.” Water 8 (6): 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/w8060219.

- “European Country of Origin Information Network — Ecoi.Net.” n.d. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/1301669/1222_1197552781_helmand-provincial-profile.pdf.

- “Global Warming.” 2010. Text.Article. NASA Earth Observatory. June 3, 2010. https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/features/GlobalWarming/page2.php.

- Gnjato, Slobodan, Tatjana Popov, Goran Trbić, and Marko Ivanišević. 2019. “Climate Change Impact on River Discharges in Bosnia and Herzegovina: A Case Study of the Lower Vrbas River Basin.” In Climate Change Adaptation in Eastern Europe, edited by Walter Leal Filho, Goran Trbic, and Dejan Filipovic, 79–92. Climate Change Management. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978–3–030–03383–5_6.

- Goes, B. J. M, S. E. Howarth, R. B. Wardlaw, I. R. Hancock, and U. N. Parajuli. 2016. “Integrated Water Resources Management in an Insecure River Basin: A Case Study of Helmand River Basin, Afghanistan.” International Journal of Water Resources Development 32 (1): 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/07900627.2015.1012661.

- “Helmand Population.” n.d. Accessed April 19, 2023. http://population.city/afghanistan/adm/helmand/.

- “Xeric Freshwaters and Endorheic (Closed) Basins.” n.d. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://www.feow.org/ecoregions/details/702.

- Xu, H., and Y. Luo. 2015. “Climate Change and Its Impacts on River Discharge in Two Climate Regions in China.” Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 19 (11): 4609–18. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-19–4609–2015.

- Yatagai, A., P. Xie, and P. Alpert. 2008. “Development of a Daily Gridded Precipitation Data Set for the Middle East.” Advances in Geosciences 12 (March): 165–70. https://doi.org/10.5194/adgeo-12–165–2008.

- https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/afghanistan/brief/afghanistan-climate-change-and-water-management.

- Geology, Water, and Wind in the Lower Helmand Basin, Southern Afghanistan (USGS 2006, repots)/ https://pubs.usgs.gov/sir/2006/5182/pdf/SIR06–5182_508.pdf

- Provincial profile for Helmand Province by Regional Rural Economic Regeneration Strategies (RRERS) https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/1301669/1222_1197552781_helmand-provincial-profile.pdf