This article discusses some of the main ideas and theories related to language anxiety and social media addiction. It also attempts to fill a gap in the existing literature by exploring the relationship between language anxiety and social media addiction among students. The study revealed a significant positive correlation (r = 0.521, p < 0.001) between these two variables. These findings suggest that students with higher levels of social media addiction may also experience increased language anxiety.

Keywords: foreign language, connection, correlation, level, social media addiction, language anxiety, anxiety, social media.

В данной статье рассказывается об одних из главных идеях и теориях, которые относятся к языковой тревожности и зависимости от социальных сетей. Здесь также осуществляется попытка заполнить пробел в существующей литературе, исследуя взаимоотношение между языковой тревожностью и зависимостью от социальных сетей у студентов. Исследование выявило существенную положительную корреляцию (r = 0,521, p <0,001) между этими двумя переменными. Эти результаты подразумевают, что студенты с более высоким уровнем зависимости от социальных сетей могут также вызывать повышенную языковую тревожность.

Ключевые слова : иностранный язык, связь, корреляция, уровень, зависимость от соц. сетей, языковая тревожность, тревога, социальные сети.

Introduction

Commencing in the 1970s, researchers initiated a dedicated exploration into the realm of anxiety, embarking on a continuous journey that endures to the present day. This ongoing commitment underscores the profound significance attributed to understanding and unraveling the intricate layers of anxiety. At its core, anxiety is delineated as an overpowering surge of intense emotions and sensations, encompassing nervousness, stress, worry, apprehension, and agitation. This sophisticated psychological phenomenon, though nuanced and multifaceted, appears as a formidable barrier that can impede the progress of foreign language learners. The labyrinth of emotions it introduces becomes a convoluted puzzle, posing challenges that necessitate a holistic comprehension for effective intervention and support in the realm of language acquisition. It is a serious problem in foreign and second language classrooms, experienced by perhaps one third to one half of students [1]. This paper elaborates on the anxiety faced by certain students within an English class, explicitly denoted as foreign language anxiety (FLA), as it aligns with the accurate terminology.

One among the myriad sources contributing to anxiety is social media (SM), and individuals grappling with social media addiction tend to manifest elevated anxiety levels. The potential impact of social media addiction, particularly in relation to FLA, has been undervalued. Our endeavors to uncover information regarding the correlation between social media addiction (SMA) and FLA have, regrettably, yielded no conclusive findings. As a result, this study represents the initial inquiry into the correlation between FLA and SMA, which in itself is the novelty of this study, constituting a unique aspect of this research. The primary goal of this investigation is to bridge the existing gap in the literature by undertaking a survey and correlation analysis, aiming to contribute to the extended exploration of FLA.

Foreign Language Anxiety

State, trait and situation-specific anxiety are the general theories of anxiety that are commonly explored in an attempt to obtain a better knowledge about foreign language anxiety (FLA). In addition, psychologists coined the term specific anxiety reaction, which is precisely identical to situation-specific anxiety in purpose and application, that is, specific anxiety reaction is what characterizes somebody who find themselves experiencing anxiety only in specific situations and if a person happens to always turn anxious mainly in the cases where language learning takes place, for instance, during an English class at a university or school, then they fall into the category of specific anxiety reactions [2]. According to P. D. MacIntyer, R. C. Gardner, the sensation of unease, tension and apprehension, especially within the realms of a second language, encompassing tasks such as speaking, listening, and learning, defines language anxiety (LA) [3]. E. K. Horwitz, a pioneer of FLA, proposed the following definition: FLA is a distinct complex of self-perceptions, beliefs, feelings, and behaviors related to classroom language learning arising from the uniqueness of the language learning process [2, p. 128]. The process of foreign language learning (FLL) is obstructed by elevated levels of FLA. P. D. Maclntyre, R. C. Gardner found that anxious students learned a list of vocabulary items at a slower rate than less anxious students and had more difficulty in the recall of previously learned vocabulary items [3, p. 285], which can be explained by a number of studies that found that FLA is able to interfere with cognitive operations. This interference hampers the ability to comprehend information, grasp new content, and demonstrate learning, particularly concerning the production of a second language [4].

When familiarizing oneself with such an extensive topic as FLA, it is essential to pay attention to the causes and effects of this phenomenon. P. D. MacIntyre concluded that FLA is both a cause and consequence of language performance [5]. Prior to reaching that conclusion, there were several studies that debated over the following question “Is it a cause or consequence?”. The starting point of the “chicken and egg” discussion about the causal relationship of the FLA and foreign language achievement was the article of R. L. Sparks, and L. Ganschow published in 1991. They perceived FLA as an inherent outcome of challenges and subpar performance in FLL. [6]. In their article they state that from their standpoint, diminished motivation, unfavorable attitude, or heightened anxiety likely stem from inadequacies in effectively managing one's native language, even though they are evidently linked to challenges in learning a foreign language (FL) [7]. However, E. K. Horwitz discovered that FLA was even suffered by those students who had a proper command of their FL, thereby indicating FLA as a cause [8].

Scholars tend to cite a variety of FLA-induced negative consequences (or effects). For instance, students with high FLA level find themselves struggling to perform well at an academic level. Furthermore, having experienced a rush of anxiety a certain number of times, the student might begin to view uneasiness or anxiety as a part of second language learning, which leads them to abandon further attempts to become more advanced learners. Besides, the aforementioned problem pertaining to cognition is one of the adverse effects as well. According to P. D. MacIntyre, students have a hard time wholly accessing their cognitive capabilities, when necessary, due to the impact of anxiety. It compels students to self-deprecate while adversely affecting 3 stages of learning, which are input, processing and output [5, p. 24].

The current study would be regarded as incomplete if the entire paragraph of causes of FLA were omitted. Among all the internal sources found as root sources of LA, the four most relevant were: their low level of competence in English, some personality traits, their fear of negative evaluation by others and their general fear of speaking in public [9]. D. J. Young presented a comprehensive perspective, identifying six principal sources that can potentially instigate anxiety among language learners. These sources encompass a spectrum of influences, ranging from personal and interpersonal anxieties to the beliefs held by learners regarding language learning. Moreover, anxiety can be influenced by the beliefs that language instructors hold about the teaching process. The dynamics between instructors and learners, the procedures employed within the classroom, and the nature of language examinations also contribute significantly to the anxiety experienced by language learners. By recognizing these multifaceted sources, D. J. Young offers a nuanced understanding of the factors contributing to anxiety in the language learning environment. [10]. In addition to the insights provided by D. J. Young, Y. Aida has delved into the intricacies of anxiety within the FL classroom, identifying a spectrum of four distinct causes. These factors encapsulate the complex emotional landscape experienced by language learners. Firstly, there is the element of speech anxiety coupled with the fear of negative evaluation, highlighting the apprehension tied to expressing oneself verbally in the presence of peers or instructors. He also sheds light on the fear of failure, a pervasive concern that can hinder the learning process. Moreover, the concept of comfortableness in speaking emerges as a noteworthy source of anxiety, emphasizing the need for learners to feel at ease during communicative activities. Lastly, Y. Aida underlines the impact of negative attitudes towards the class itself, recognizing the potential influence of overall perceptions on the anxiety levels within the FL learning environment [11]. Also, K. M. Baily was the first scholar who attempted a different investigation approach, which was to examine FLA from children’s point of view and the conclusion was that children have a competitive nature, due to which anxiety can be brought about because they possess a high degree of proneness to comparing themselves or viewing themselves as perfect and ideal. Similarly, worry and fear to fall victim to the negative comments and remarks or evaluation from the classmates result from low self-esteem [12]. At last, E. K. Horwitz et al., as a part of her FLA theory, proposed three situation-specific anxieties, namely, communication apprehension, fear of negative evaluation and test anxiety. By many, they are considered as the underlying components of FLA, albeit E. K. Horwitz herself doesn’t concur, presenting them only as related to FLA [1, p. 127].

Social Media Addiction

The worldwide number of social media (SM) users has reached a unprecedented 4.9 billion people, and estimates suggest it will rise to around 5.85 billion users by 2027. Within this context, social media addiction (SMA) has gained significant prevalence, impacting up to 210 million individuals with negative outcomes [13]. SMA is the other variable examined in the current paper. SMA is a behavioral addiction that is defined by being overly concerned about SM, driven by an uncontrollable urge to log on to or use SM, and devoting so much time and effort to SM that it impairs other important life area [14].

Certainly, since the integration of social media into our daily lives, humanity has had the opportunity to experience the multitude of benefits it offers. In spite of all the advantages that SM has; regardless of how authentic communicating online with somebody feels; ultimately students might grow more disappointed about their SM, being unable to feel as emotionally fulfilled. This occurs because those positive emotions might turn out that they were short-lasting. D. Kardefelt-Winther put forward a theory on compensatory internet use, suggesting that adverse life circumstances can lead to a motivation to use the internet as a means of alleviating negative emotions. The fundamental principle of the compensatory internet use theory posits that the individual's response to their negative life situation is facilitated by an internet application. For instance, in a scenario where real-life lacks social stimulation, the individual responds with a motivation and desire to engage online for socializing, facilitated by an application that enables social interaction [15]. Moreover, SMA is motivated by the need to fulfill fundamental psychological needs that cannot be gratified in the real world, such as the need to belong [16].

In the domain of SMA literature, depression is a commonly investigated psychiatric condition. Likewise, anxiety is another psychiatric condition that is frequently studied [16]. Individuals with anxiety that tend to evade social settings find themselves addicted to SM and as their addiction grows and solidifies, the level of their social skills declines. People that deflect any opportunity to talk to somebody in-person, withdrawing on SM, in fact, do desire to have a conversation offline, however, they fear and as a result of it, they spend the most of their time online, gratifying their desire to talk to people by these means. Additionally, C. T. Barry et al. explored the associations between the use of social media by adolescents and their psychosocial adjustment. Social media activity showed to be positively and moderately associated with depression and anxiety [17]. H. Yan et al. found that insomnia played a meditating role on the significant correlation between depression and addiction to social media. In addition, H. Yan et al. found a significant positive correlation between more than a 2-hour use of social networks and the intensity of anxiety. Further, engaging with social media, encountering an enormous number of photos on social media shared by people who appear to have a more prosperous life feeds our inclination to compare ourselves with others and worsens our emotional welfare [18].

FLA and SMA

A. A. Mansour et al. found a significant positive association between SMA and symptoms of anxiety. The finding is aligned with previous research performed among students from different countries. A plausible explanation of this finding is that overusing social media encourages prolonged platform browsing, which could lead to risky behaviors such as sleep deprivation and eventually enhance negative psychological reactions [19]. F. F. Muhammad et al. established a significant strong association between general anxiety disorder and SMA. Furthermore, in a correlational study they concluded that passive social media use was positively correlated with social anxiety [20]. Furthermore, an additional correlational investigation delved into the areas of social appearance anxiety, automatic thoughts, psychological well-being, and SMA.

People constantly evaluate themselves and others in terms of intelligence, achievement, wealth, social standing, and appearance [21]. SM makes users more prone to comparing, saturating their social media feed with the photos of others. There were two studies on the correlation between Facebook and self-esteem and two of them found a negative correlation. In other words, the people who engaged much more with SM had lower self-esteem. That can be interpreted by what C. Yang et al. states, explaining that the more we watch those who seem better off on social media, the worse off we are, therefore SMA could clearly lead to self-comparison and psychological problems [22]. For instance, low self-esteem, low self-efficacy etc.

Low self-esteem thus implies self-rejection, self-dissatisfaction and self-contempt [23], and is also another problem for students, which causes anxiety. Students encumbered with low self-esteem tend to be afraid of teachers’ and peers’ judgement or/and evaluation as their self-evaluation and their perception of how proficient they are and the way others evaluate them contradict each other, for that reason, they decide to stay silent. All of the above eventually leads up to the hypothesis of this study that states that the more addicted students are to SM, the higher level of FLA they have, therefore there must be a positive correlation between FLA and SMA. Additionally, the significance of the current study is that FLA has always posed a great challenge to both teachers and students, hence attempts to gain more and more insight into that phenomenon should be continued and this study attempts to look at it from a different angle and make a contribution to further exploration of the matter.

Methods

This study employed quantitative research to collect and analyze data. To conduct this research, first of all, it was essential that data be gathered through surveying. 80 respondents partook in this survey, all of whom are students from 2-nd year to 4-th year students. 30 respondents are studying in Russian, the rest 50 respondents are studying in Kazakh.

For the survey, Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale (FLCAS) designed by E. K. Horwitz et al. was adopted along with Social Media Addiction Scale (SMAS) designed by A. T. Ünal, L. Deniz. The SMAS demonstrated a high level of reliability, as evidenced by the calculated Cronbach's Alpha value of 0.967 [24]. A meta-analysis conducted by Teimouri revealed consistent results across numerous studies. In this analysis, approximately 80 studies utilized Cronbach’s alpha as a reliability index, with all of them reporting 0.97, indicating a consistently high level of reliability [25].

FLCAS was used to assess participants FLA level and The questionnaire included 33 questions on a 5-point Likert scale; SMAS was used for identifying students’ SMA level and was made up of 41 questions on a 5-point Likert scale.

Both of the scales were translated into Russian before they were distributed among all the participants. That was a necessary measure to avoid skewed results from answers, since not all students had similar English levels. Having collected all data, JASP 0.18.0.0 was later used to conduct correlation analysis.

Results

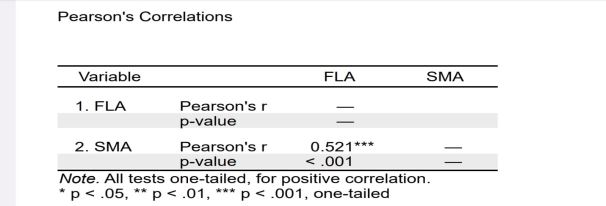

Table 1

To discern the nature of the correlation between SMA and FLA, the Pearson correlation coefficient was employed to achieve the predefined goal. Upon meticulous scrutiny of Table 1, a conspicuous revelation unfolds, which is a high positive correlation between FLA and SMA, denoted by the coefficient value (r = 0.521). Delving further into the results, additional information is provided to expound upon and illuminate the strength of the correlation, serving as a comprehensive guide. The delineation suggests that 0.0 < r < 0.1 signifies no correlation; 0.1 < r < 0.3 implies a little correlation; 0.3 < r < 0.5 denotes a medium correlation; 0.5 < r < 0.7 indicates a high correlation; and 0.7 < r < 1 signifies a very high correlation [26].

Notwithstanding the robust positive correlation between these variables, it is imperative to underscore that correlation does not imply causation. It is crucial to refrain from attributing one variable as the cause of the other, as they are inherently and simply correlated. Additionally, the noteworthy significance level of p < 0.001 attests to the statistical importance of the observed correlation between the two variables, adding another layer of depth to the analytical findings.

Conclusion

This study was limited in different ways. First, the sample number was quite small. Attempting to make conclusions based on merely eighty participants may potentially lead to false positive results. Second, in the sample the number of females (73) immensely outnumber males (7). Third, the results might have been skewed due to some participants’ native language, which was Kazakh. Fifty participants with the Kazakh native language were surveyed in Russian, i.e., the questions were in Russian.

This paper primarily discussed the main theories and ideas of both SMA and FLA. It aimed to investigate the correlational relationship between FLA and SMA among university students. The research sought to bridge a gap in the existing literature by studying whether students who have higher levels of SMA are more likely to display elevated levels of FLA.

The results revealed a statistically significant positive correlation between FLA and SMA. This result suggests that students who are more addicted to social media are more prone to encountering anxiety in the context of foreign language learning, and vice versa. It's vital to stress that this discovery doesn't establish a causal relationship.

Various factors could elucidate this connection. First, increased levels of social media addiction might result in devoting an immoderate amount time to social media, which may negatively impact students' time management and academic performance. Anxiety associated with academic difficulties may then transfer to the FL classroom, contributing to FLA.

Second, social media platforms often encourage users to compare themselves with others, fostering feelings of inadequacy and lower self-esteem. These negative emotions can translate into increased anxiety, particularly in a classroom setting where students may feel judged or evaluated.

For students, understanding the relationship between FLA and SMA can help them take steps to manage their social media usage more effectively and reduce potential anxiety. Recognizing the link between these two variables empowers students to make informed decisions about their online habits.

References:

- Renee V. W. An investigation of students’ perspectives on foreign language anxiety: dissertation / George Mason University — Richmond, Virginia, 1998. — 180 p.

- Horwitz K. E., Horwitz M. B., Joann C. Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety // The Modern Language Journal. 1986. № 2. P. 125–132.

- MacIntyer P. D., Gardner R. C. The Subtle Effects of Language Anxiety on Cognitive Processing in the Second Language // Language Learning. 1994. № 2. P. 283–305.

- Zaved A. K., Shahila Z. The Effects of Anxiety on Cognitive Processing in English Language Learning // English Language Teaching. 2010. № 2. P. 199–209.

- MacIntyre P. D. An Overview of Language Anxiety Research and Trends in its Development». New Insights into Language Anxiety: Theory, Research and Educational Implications / edited by C. Gkonou, M. Daubney and J. Dewaele, Bristol, Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters, 2017. P. 11–30.

- Kráľová Z., Petrova G. Causes and consequences of foreign language anxiety // The XLinguae. 2017. № 3. P. 110–122.

- Sparks R. L., Ganschow L. Foreign Language Learning Differences: Affective or Native Language Aptitude Differences? // The Modern Language Journal. 1991. № 1. P. 3–16.

- Horwitz E. K. It ain’t over ‘til it’s over: On foreign language anxiety, first language deficits and the confounding of variables. The Modern Language Journal. 2000. № 2. P. 256–259.

- Elena G., Enrique L. Sources of Foreign Language Anxiety in the Student-teachers’ English Classrooms: A Case Study in a Spanish University // Revista Electrónica de Lingüística Aplicada. 2021. 161 p.

- Young D. J. An investigation of students’ perspectives on anxiety and speaking // Foreign Language Annals. 1990. № 6. P. 539–553.

- Aida Y. Examination of Horwitz, Horwitz and Cope’s construct of foreign language anxiety: The case of students of Japanese // The Modern Language Journal. 1994. № 2. P. 155–168.

- Baily K. M. Competitiveness and anxiety in adult second language learning: Looking at and through the diary studies // edited by H. W. Seliger, & M. H. Long, Classroom Oriented Research in Second Language Acquisition. 1983. P. 67–102.

- Top Social Media Statistics and Trends Of 2023. Forbes [Online source]. URL: https://www.forbes.com/advisor/business/social-media-statistics/ / 2023 (access date: 05.11.2023).

- Social Media Addiction. Addiction Center [Online source]. URL: https://www.addictioncenter.com/drugs/social-media-addiction/ / 2023 (access date: 05.11.2023).

- Kardefelt-Winther D. A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: towards a model of compensatory internet use // Computers in Human Behavior. 2014. № 1. P. 351–354.

- Cheng C., Ebrahimi O. V., Luk J. W. Heterogeneity of Prevalence of Social Media Addiction Across Multiple Classification Schemes: Latent Profile Analysis [Online source]. URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8787656/ / 2022 (access date: 04.11.2023).

- Barry, C. T., Sidoti, C. L., Briggs, S. M., Reiter, S. R., Lindsey, R. A. Adolescent social media use and mental health from adolescent and parent perspectives // Journal of Adolescence. 2017. № 1. P. 1–11.

- Yan H., Zhang R., Oniffrey M. T., Chen G., Wang Y., Wu Y., Zhang X., Wang Q., Ma L., Li R., J. B. Moore Associations among Screen Time and Unhealthy Behaviors, Academic Performance, and Well-Being in Chinese Adolescents // Environmental Research and Public Health. 2017. № 6. P. 1–15.

- Mansour A. A., Naif S. A., Najim Z. A., Amar A. A. A., Mohammed R. A, Abdulelah S. Y. A. Q., Mohammed A. A., Faisal T. G. A. Prevalence and Determinants of Social Media Addiction among Medical Students in a Selected University in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study // Healthcare. 2023. № 10. P. 1–17.

- Muhammad F. F., Hina J., Sara I. Relationship between Social Media, General Anxiety Disorder, and Traits of Emotional Intelligence // Bulletin of Education and Research April. 2022. № 1. P. 39–53.

- Han Q. Social Comparison and Well-Being under Social Media Influence // BT — Proceedings of the 2022 8th International Conference on Humanities and Social Science Research. 2022. P. 633–636

- Yang C, Sean M. H., Mollie D. K. C., Jessica J. Social media social comparison and identity distress at the college transition // Adolescence journal. 2018. № 1. P. 92–102.

- Lee J. Y., Patel M., Scior K. Self-esteem and its relationship with depression and anxiety in adults with intellectual disabilities: a systematic literature review // Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2023. № 6. P. 499–518.

- Ünal A.T, Deniz L. Development of the Social Media Addiction Scale // AJIT-e Academic Journal of Information Technology. 2015. № 21. P. 51–70.

- Teimouri Y., Goetze J., Plonsky L. Second language anxiety and achievement: A meta-analysis // Studies in Second Language Acquisition. 2019. № 2. P. 363–387.

- Correlation analysis. Datatab [Online source]. URL: https://datatab.net/tutorial/correlation / 2023 (access date: 08.11.2023)