Commercializing the innovations is vital not only for Russian science, but for the national economy as a whole. In this paper authors concentrate on some challenges of commercializing Russian innovations and give a brief overview of current situation in this field. A short comparative analysis with other countries is provided. Further on the authors specify forms of education, science, and business integration, define challenges and opportunities in the process of commercializing the innovations.

Key words: innovative economic development, scientific research, commercializing the innovations, intellectual property, innovation index, innovative infrastructure, technology parks, Naukagrads, small innovative enterprises.

Nowadays, the problem of innovative economic development and application of results of scientific research in national economy is of major importance for both the Russian scientific community and the entire economy of our country.

The reforms undertaken to make the Russian economy market-oriented, have changed the direction of scientific efforts in this country. The main point lies in decentralizing the science management system and modifying the financial profile of scientific research.

Though the changes brought about by the reforms were quite radical, Russian science is still controlled by the governmental authorities. Most of the local scientific centers and testing laboratories are publicly owned. Moreover, scientists’ wages are paid from state-owned funds. In this respect, Russian science differs from science in the West, where the bulk of research is carried out by private scientific centers and laboratories.

At the same time, Russian science is poorly financed — it gets about 5–10 % of the funds required. This demonstrates the need for reorganizing the whole R&D financing scheme and for attracting angel investors to financing Russian research, with granting some rights for the future products to such investors.

In fact, private investments in science stipulate acquisition of ownership rights for a specific product — intellectual property. Such ownership may bring significant benefits to investors. In order to create this specific product, scientific projects should be “wrapped up” in an appropriate “package”. As a minimum requirement, one should explore the market situation and financial conditions.

The process of investing funds into promising scientific projects is called ‘commercialization of technologies’ and is supposed to include search for, expert evaluation of and selection of projects deserving financing. The commercialization encompasses also attracting investments, assigning the rights for the future intellectual property and distributing such rights between the partners taking part in the process. Moreover, the commercialization should include managing the scientific projects and connecting the results of research with the production process.

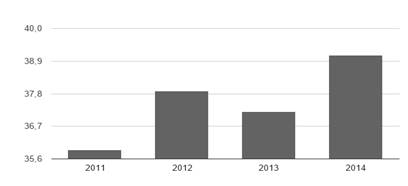

There is a special indicator — Innovation Index — showing development in the sphere of innovations. It is calculated by Cornell University, INSEAD, and WIPO for Russia. The chart below (Fig.1) shows that from 2011 to 2014 the amount of innovation investments in Russia has increased dramatically. [10]

Figure 1. Cornell University Innovation Index for Russia

But at the same time the situation in Russia is rather unfavorable, if compared to other countries. Great Britain is at the top of the list, the runner-up is the USA; the 3rd place belongs to Canada, the 4th to Germany, the 5th to Australia. And Russia is on the last place with a much lower innovation index.

Unfortunately, in Russia science is isolated from business. Therefore, technological development is not directly connected with the manufacturers’ needs. Moreover, scientists are not aware of the manufacturers’ needs and cannot predict if the product released as a result of their research, will justify the investments or not.

Commercializing the innovations is vital not only for Russian science, but for the national economy as a whole. Time has come for the producers to be interested not so much in the quantity of goods produced, but in the unique quality of their goods if they are going to provide the nation’s economy with a competitive advantage.

A great part of new problems concerning the Russian innovative infrastructure arises from the disputes between such ‘members of the economic panel’ as the academic community, business structures, universities, and government of the Russian Federation. The following issues are in the focus of attention: “Which form of socio-cultural integration is most suitable for our country’s specific situation?” “What mechanism of cooperation between state, business, and science would be most effective under the current circumstances and in the future?” [5]. These issues have been discussed again and again at various forums and conferences as well as highlighted in numerous reports of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation. Their brief overview is given below.

The first problem identified was that of time. In the USA, the origin of science and business integration goes back to the 1950s when Frederick Terman, Provost of Stanford University, decided to lend plots of land to graduates. [1, p. 23–26] A strong link between private companies and the university was established, which eventually resulted in creation of the technology park now known as “the Silicon Valley.” [2, 4] At present Russia does not have the luxury of devoting over a half-century to developing the innovative process.

The second problem is the lack of experience. Before the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, there was no market system in our country, so there was no mechanism to promote and facilitate cooperation between private business, state, and science. As for Academic Towns, such as Dubna, which, during the period of the Soviet planned economy, were considered autonomous institutions, there were still no strong ties between science and state-owned businesses, nor between science and the state education system. The state was the main consumer of scientific innovation and scientific knowledge had a narrow focus. The governmental bodies kept a tight rein on science, which was considered to have no commercial role at all.

Academic Towns specialized in scientific research that was usually kept secret and the knowledge resulting from that research usually did not go outside the campus and certainly did not penetrate into the mass education system of the Soviet state.

By the end of 1980s and in the beginning of the 1990s, this factor resulted in a “brain drain” which was typical in such fields as physics and space research. By the early 1990s, the USA experienced a lack of scientific and technical specialists, and the immigration of Russian scientists as well as scientists from South Korea, Japan, and India into the US filled the gap.

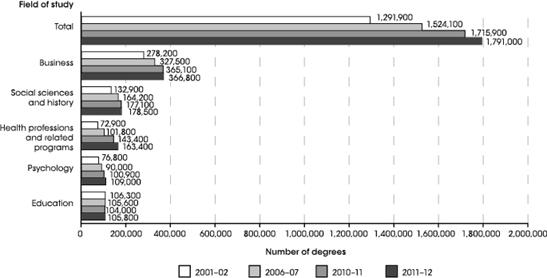

However, the higher education in the USA today is suffering from a numerical imbalance between the humanitarian experts and experts in the engineering sciences.

Figure 2. Number of bachelor's degrees awarded by Title IV postsecondary institutions in selected fields of study

Academic years 2001–02, 2006–07, 2010–11, and 2011–12. U. S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), Fall 2002, Fall 2007, Fall 2011, and Fall 2012, Completions component. [7]

These five fields were selected because they were the fields in which the largest percentages of bachelor's degrees were awarded in 2011–12. The data are given for postsecondary institutions participating in Title IV federal financial aid programs. The new Classification of Instructional Programs was initiated in 2009–10. The estimates for 2001–02 and 2006–07 have been reclassified, when necessary, to make them conform to the new systematization. ‘Business’ includes business, management, marketing, and related supporting services as well as personal and culinary services.

All in all, the number of specialists in the humanities is much larger than those entering the science, technology, and engineering fields.

Infrastructure constitutes the third problem, which has been with us in Russia from the outset. Former Academic Towns (some of them became later ‘Naukograds’, scientific townships) were scattered around the vast territory of our country and inherited their particular specialization from the old, Soviet model. More often than not, this specialization was in a certain field inherited from the USSR along with the town’s infrastructure. For that reason, it is now necessary to create new science centers where various technological and scientific resources would be concentrated in order to meet the new demands and to provide profitability.

The forth problem is our ‘brain drain’. Despite the commonplace view that the wave of scientific and technological emigration from Russia has decreased, it is not true. The group of Russian physicists, including the Nobel Prize winner of 2010, K. Novoselov, who has moved to Great Britain, is a vivid example. There is no doubt that the number of science emigrants has become less at least for the reason that other countries have already filled their scientific staff vacancies, but Russian scientists are still looking for new places of permanent residence — for a variety of social, economic, and political reasons. [9]

All these problems, as well as many others, have compelled the Government of the Russian Federation to start creating a new infrastructure, which would provide possibilities of commercializing the results of scientific research. The government is certainly interested in new scientific achievements because the Russian economy’s dependence on exporting the raw materials is becoming, more and more, a factor that is slowing down the innovative development in Russia. The outward stability that has existed in Russia so far depends on the high prices for Russian-produced oil, gas and other energy resources, but not on our new technologies.

Further on the authors will concentrate on specific forms of education, science, and business integration.

On September 28, 2010, the then president of Russia, D. A. Medvedev, signed Federal Bill # 244, ‘Concerning the Innovation Center at Skolkovo’. The bill came into force as a law on September 30 that year. [3] The idea of creating an innovation center was proposed to the Russian Government by Maxim Kalashnikov, a Russian politician, public figure and journalist, who addressed the president through an open letter in which he presented his own vision for the future of Russian science in the form of a “Futuropolis” or city of the future. [3] By the end of 2010, both the Chambers of the Russian Parliament worked out the necessary bills providing the legislative ground for a full-fledged and functioning Skolkovo. On March 23, 2011, in California, an innovation center was opened to promote cooperation between Skolkovo and interested organizations in the United States of America. At present, there are heated discussions about the role of the innovation center at Skolkovo.

Despite the good intentions of Skolkovo’s managers and of the Russian government, the innovation center itself can hardly be compared to “Silicon Valley” either in physical appearance or in organizational structure. Our model resembles Japanese techno-cities (such as Tsukuba, “the City of the Brain”), only in miniature, but it is impossible to draw a direct comparison, because Skolkovo is a unique project. It is a typical feature of the Russian character to feel shy about our inventions and to disguise them as Western ones. It is important to remember that Russia exists between two ‘universes’, Europe and Asia. That is why many of our inventions have a so-called “double context.”

A book written by E. Neborsky — ‘US Universities: Educational and Scientific Centers: A Monograph.’ [1], — gives a detailed description of the American and Japanese forms of centers encompassing education, science, and business integration — since they are specific.

The first form of such centers he describes is an American one based on the patronage principle and is called a “research university.” This type of a center arises when a university, such as the famous Massachusetts Institute of Technology, accumulates around itself some business incubators, research laboratories, and so on. The university plays an active role as a coordinating facilitator between business and science.

The second form is also an American one based on the partnership principle and is called a “technology park.” (A park’s name depends on its inner structure.) A “technology park” or “techno park” can be self-structured, as is the case with “Route 128.” In this case, the university plays a leading role in its active partnership with business.

The third form is Japanese and is based on the principle of neighborhood and is called “Technopolis.” It originated in Japan during the 1980s and is aimed at accelerating the development of science. The same thing is now going on in Russia. There are laboratories, universities, business incubators, etc. located together at “Technopolis.” The main role in developing such a form of integration was played by the Japanese government, specifically by the Ministry of Foreign Trade and Industry, which made a request for particular research and development and then attracted big private companies to cooperation. In other words, it worked as a mediator between science and business.

In the first form of integration described above, the link with the business was provided by the university, which was interested in promoting its own alumni. Universities often share in ownership of “start-ups” which are original ventures where new technology is being introduced. In the second form previously described, the link between a university and business is ensured by some governmental “technology promotion office.” The third form, the Japanese one, supports links between the nominal structure elements through various agreements between universities and private companies. In this particular case, the laboratories situated on the land property of the “Technopolis” or near the cooperating university, are nationalized and belong to the state. The university itself does not have the capabilities to attract investments from private companies. Education remains its main function. [1, 135–143]

Unlike the above-mentioned forms, Skolkovo represents an entirely new type of innovation center. In this center, the leading role is played by the government providing financial support or, as managers of Skolkovo call it, financing is done through the state “endowment fund” obtained from the government for scientific projects selected on a competitive basis. At the initial stage of its development, this form is most suitable for Russia since it provides the country with a possibility of boosting the development of science and technology.

As it was stated above, Russia, like Japan some time ago, does not have the luxury of using a long period for a gradual, natural development allowing science to form its own relations with business. The interference of the Japanese government into relations between national science and business within a particular historical period did no harm. On the contrary, it stimulated the “Japanese Miracle.” The same principle can be applied in Russia. With appropriate management and sufficient financing, the Skolkovo and other innovation centers will hopefully be able to catch up with the world leaders in certain scientific fields and even provide for development of new technologies which may help Russia to get rid of its reliance on the exploitation of its raw material resources for supporting a major portion of the nation’s economy. Achievement of success depends on the talent of our scientists and appropriate financial management.

One more problem for commercializing innovations is certainly the global economic crisis and complicated political situation in Russia (the sanctions imposed by the USA and European countries have affected our economy badly; moreover the image of Russia is becoming very uncertain, so investors may fear to take high risks of investing in our innovative projects). The shaky state of world economy has a negative impact on implementation of innovations and investments in this field, because corporations try to reduce their possible risks. Russia is still low on the list of nations characterized by innovation. According to the Bloomberg ratings agency, the list is topped by South Korea surprisingly well ahead of other nations, the second place belongs to Sweden. Then follow the United States, Japan, Germany and Denmark. Russia is only on the 18th place. But where is China? It is in the 25th place in the overall innovative rating, but in the first place in manufacturing capability as regards innovations. The negative global economic situation has slowed down the development of innovation environment in Russia trying though to further reorient itself towards new economic guidelines, including the development of human potential. [6]

In Russia, there is a variety of “key players” in the process of commercializing the innovations [8]:

1. Russian industry.

The Russian enterprises are the main developers and consumers of innovations. In 2010, Russian industry used 78 % of the overall volume of industrial technologies, due to a fierce competition on the market. And, as it usually happens in a market economy, this competition leads to the development of innovations.

2. International industry.

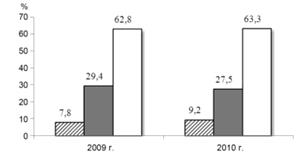

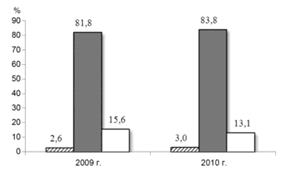

International enterprises are both importers and exporters of innovative technologies. (Fig.3, Fig 4)

Figure 3. Share of various countries in the structure of Russian export:  - CIS,

- CIS,  - OECD (an international economic organisation of 34 countries founded in 1961 to stimulate economic progress and world trade),

- OECD (an international economic organisation of 34 countries founded in 1961 to stimulate economic progress and world trade),  - other countries

- other countries

Figure 4. Share of various countries in the structure of Russian import:  - CIS,

- CIS,  - OECD (an international economic organisation of 34 countries founded in 1961 to stimulate economic progress and world trade),

- OECD (an international economic organisation of 34 countries founded in 1961 to stimulate economic progress and world trade),  - other countries

- other countries

3. Consumers.

Consumers are the end users of innovative technologies. In the past, Russian economy was not oriented towards consumers’ needs. The economy was interested only in supporting the national security, heavy industry and extraction of raw materials. But now the innovations are becoming more numerous, varied and commercialized.

4. Government.

The Russian government is the main consumer of innovations in the country. It makes governmental orders for innovative products. However, our expenditures on innovations are less than a half of what the USA is spending.

5. Universities and science centers.

Nowadays universities are becoming more oriented towards needs of the market, organizing their own small firms for the purpose of commercializing the innovations.

6. Intermediaries.

Intermediaries help to connect innovations with the market. Intermediaries include patenting and licensing agencies, consulting and marketing firms (offices for commercializing the innovation, business incubators, and innovative technologies centers). A system of intermediaries is developing in Russia now.

Over the centuries, Russian science has made many valuable contributions to the world science. It is therefore reasonable to hope that the development of innovation in Russia will accelerate and will soon enable Russians to join the ranks of leaders in technological innovation — such as the USA, Germany, China, and Japan.

And there are some reasons to state that it is really possible for Russia to become one of the world’s innovative leaders. But how can it be achieved?

Firstly, the slow commercialization of innovations in Russia suggests that our nation’s potential in this sphere is not used completely. Russia is traditionally considered to be a country with a high level of education and science. In some spheres of knowledge, our scientists are among the world’s best ones. Moreover, we have many talented people with unique technological ideas and insights.

Secondly, owing to the low development of the intellectual property market in Russia and the deplorable lack of information, (scientists do not know enough about their rights and the price of their concepts and ideas), Russian innovative technologies are considerably cheaper than innovations abroad. It can also be explained by the Russian scientists’ small salaries and the relatively low standard of living in the country.

Thirdly, many innovations that were kept secret in the USSR are being declassified and disclosed now.

The most effective way to improve commercializing the innovations in Russia is to create a greater number of small innovative enterprises.

References:

1. Neborsky E. ‘US Universities: Educational and Scientific Centers: A Monograph.’ Saarbrücken: LAP Lambert Academic Publishing, 2011. 180.

2. Neborsky E. “Economics of Education in the USA: University and Capitalization: A Monograph.” Saarbrücken: LAP Lambert Academic Publishing, 2012. 76.

3. Petlevoy V. “The Skolkovo Fund will spend 50 billion rubles in 2012.” Moscow: RBC-Daily. Dec. 20, 2011. URL: http://www.rbcdaily.ru/2011/12/20/media/562949982336143.

4. Stewart Gillmor. “C. Fred Terman at Stanford: Building a Discipline, a University, and Silicon Valley.” Stanford University Press, 2004. 672.

5. Tech — business online magazine. URL: http://www.techbusiness.ru/tb/archiv/number7/page11.htm

6. BLOOMBERG RANKINGS. URL: http://images.businessweek.com/bloomberg/pdfs/most_innovative_countries_2014_011714.pdf

7. National Center for Education Statistics. URL: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cta.asp

8. “Open Science” association. URL: http://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/problemy-i-spetsifika-kommertsializatsii-innovatsiy-v-rossii-na-sovremennom-etape-razvitiya

9. Russian — American education forum: an online journal. URL: http://www.rus-ameeduforum.com/content/en/?task=art&article=1000894&iid=11

10. The Global Economy site. URL: http://ru.theglobaleconomy.com/Russia/GII_Index/