Education is the pillar of society that opens the door to progress. Students’ academic success largely depends on resources available to them and their environment. This research focuses on how the type of the school, familial legacy and income as well as psychological setting among peers affect children’s access to education. The participants of the study were secondary school students and educational professionals. The duration of the study was six months. The results showed that the financial situation of the family and the environment influence both the quality of education received by children and their motivation to learn

Introduction

If an individual was born in a poor family, can they really succeed by working hard to gain knowledge on their educational path? Recent trends suggest that it is not enough as social inequality levels rise, affecting children’s education. Only in the US fall of 2020 college enrolment rates for low-income students plunged at rates nearly double that for students from higher-income high schools [1].

Recent research has emphasised the importance of education in ensuring social stability, inclusion and equity [2]. However, the majority of studies focused on adolescents and young adults receiving higher education but not schoolchildren. School is a starting point of any life path, so the examination and eradication of inequality causes should start there. Kazakhstan is a developing country providing free primary and secondary education. However, the difference in the quality of education in public and private schools is high [3], which strongly affects students’ future enrolment into the university and success in life.

Context

Education is one of the most crucial factors strengthening socio-economic growth and empowering generations with skills and knowledge. The growing recognition of equal opportunities for people from all social backgrounds increases the need to recognise and address educational inequalities. The following review confirms that the educational inequality problem is influenced by parental socio-economic status and educational background, which in turn affect children psychologically.

During the 21st century, education experienced radical transformation from internal structure to teaching methods [4]. Numerically, these changes were beneficial. A century ago, only a small fraction of the population was educated. These days, as Bloom and Cohen note, “progress towards universal education has been unprecedented. Illiteracy in the developing world has fallen from 75 % of people a century ago to less than 25 % today” [5].

However, the permission for, and subsequent expansion of, private schooling has consequences beyond the involvement of private actors in the education. These include a mostly socio-economically homogeneous student body — with high income families in private and middle and low income in public schools — that creates psychosocial differences in the mentality of students [6]. However, Pakistani researchers have concluded that there is no significant difference between the satisfaction of public and private school students with the services of their school [7]. It is connected to the overall educational system of Pakistan: Pakistan is still far below universal primary education quality [8], so, in fact, all sectors — public, private, institutional — lack quality of services.

These correlations led to further investigations on intergenerational mobility examining how one’s financial state affects the education of their offspring. Finnish scientists found that individuals whose parents have high incomes (especially men) are more likely to remain in the higher income class, despite lower educational achievement [9]. At the same time, US researchers confirmed that there is a strong relationship between low-income family background and lower education achievements [10]. They found that greater levels of financial inequality could lead youngsters to believe that investment in their self-development yields a lower rate of return. Similarly, a UK study found that “children who experience parental social mobility, either up or down, during their school years attain levels of qualifications in later life that lie between those from families who remained stable in the relevant classes of origin and destination” [11].

Future success of children is also mediated by parental background psychologically. McKown and Weinstein [12], Désert, Préaux and Jund [13] observed that children from a disadvantaged social class underperform at school when faced with stereotype threat.

Millions of children around the world are doubting their future success because of the environment surrounding them. Unfortunately, little to no research has been conducted in Kazakhstan on the impact of social state on children’s education and ways to improve current order. Further research is needed to more clearly classify drawbacks of educational policies and address changes in regulations for todays and tomorrow’s generations.

Aims

Once an individual becomes aware of being the object of a negative group stereotype, his or her performance on the relevant test may deteriorate [13]. Consequently, if children from low-income families are conscious as early as primary school of negative reputation regarding their social status, they would already be susceptible to being victims of their own lack of confidence in any success at school. Hence, the purpose of this study is to deduce the relationship between family social strata and children’s access to education. The following questions are considered for this purpose:

Main research question:

— How does family social status influence children’s access to education in Kazakhstan?

Research sub-questions:

- What family background factors do affect children’s access to quality education?

- In what ways does family social status affect the education children receive?

- What is the impact of educational inequality on children’s academic success?

Methods

An online questionnaire was used as the main data collection method to measure the correlation between family background and children’s academic performance as well as a type of school and children’s psychological state. The questionnaire consisted of 3 parts: general questions, including information about the type of respondent’s school (public, private, or NIS) and his or her parents’ educational background, questions about academic performance and parents’ educational background and questions asking if a respondent’s family is able to purchase certain household items.

Individual semi-structured interviews were used to understand the stance of observers on a subject (educational inequality and its roots). Interviewees were selected according to the following criteria: experience in the field of education, direct communication with students and willingness to cooperate (consent to be interviewed). These qualities guarantee that an interviewee has enough of expertise in education and has his or her own vision on the subject. The interviews started off with general questions to set interviewees in a comfortable position, followed by open-ended questions which resulted in detailed answers from the respondents on their understandings of the access to education in Kazakhstan.

Results

54 high school students participated in the survey; 19 responses were received from Nazarbayev Intellectual School (NIS) students, 18 from public school students and 17 from private school students. The respondents' ages ranged from 14 to 18, with an average age of 15.7.

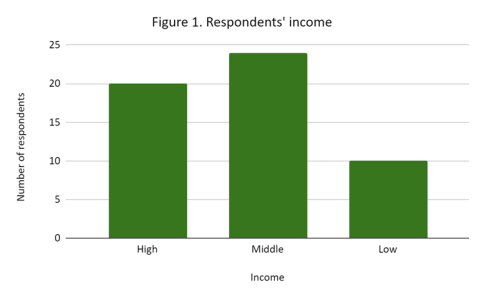

The family income of the respondents was calculated based on the answers to questions 7–11. If the respondent answered that his/her family could purchase a property without a loan, he/she was classified as a high-income student. If the respondent's family cannot purchase real estate without external sources, but can purchase personal transport (without taking a loan), he/she was classified as from a middle-income family. If the respondent's family cannot purchase household appliances without external assistance, he or she was categorised as low-income student (Anderson et al, 2018). Accordingly, 24 respondents were categorised as middle-income class, 20 as high-income class and 10 as low-income class (Figure 1).

Fig. 1

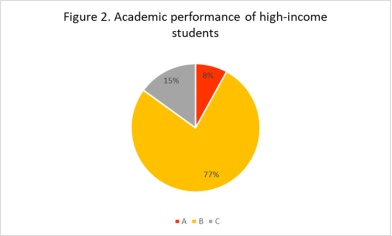

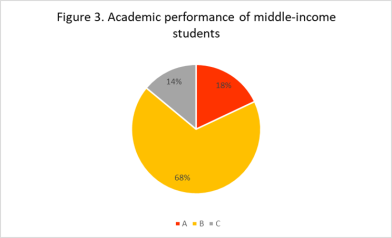

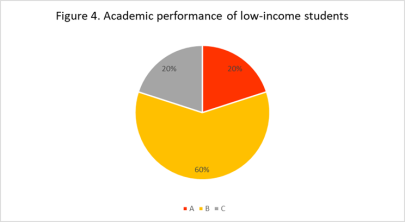

The majority of the participants were B students (Figures 2, 3, 4). The highest proportion of A and C students was of low-income descent (Figure 3). The least number of straight A students was from high-income class (Figure 2).

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

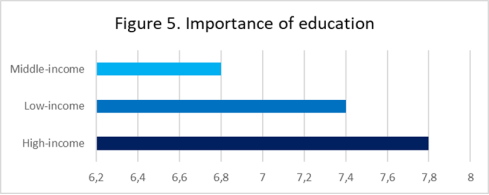

It appears from Figure 5 that students from high-income families care about their education the most (7.8 points out of 10). However, the difference in importance of education for low-income and high-income students is insignificant — only 0.4 points, whereas the difference between high-income and middle-income students is 1 point.

Fig. 5

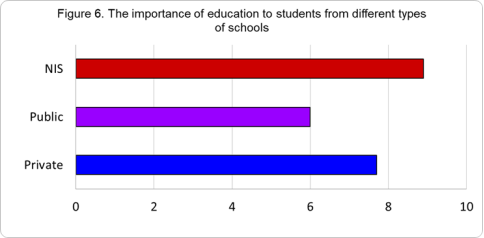

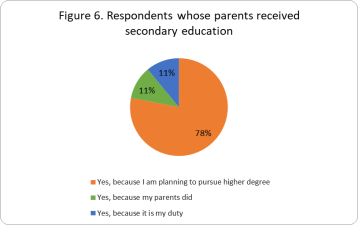

The next part of the survey investigated the differences between students attending different types of schools. According to Figure 6, the NIS students care about their education the most (9 points out of 10), while students of public schools — the least (6 points).

Fig. 6

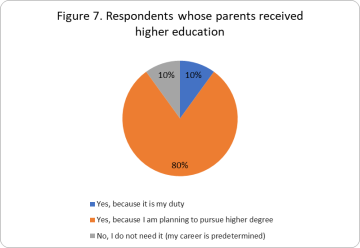

Fig. 7

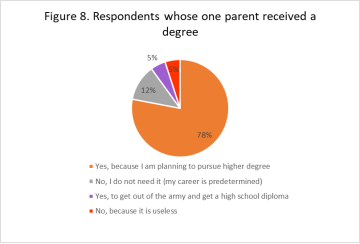

Fig. 8

The maximum number of years of work among interviewed professionals was 40, and the minimum was 3 years. There were 2 participants from private schools, 2 from NIS and 3 from public. According to participants’ responses, most of the students lagging behind the school curriculum are either in the “wrong company of peers” (meaning each member encourages underperforming in the class) or from dysfunctional families. They also attribute this to low motivation and lack of interest from parents. Specialists working with pupils in public and public schools also noted that those pupils whose future is predetermined care less about their academic performance. This is also noticeable among students from very poor and wealthy families.

Most respondents said that the environment strongly influences students' academic achievement in the long term. As one interviewee said “while the kids are in class it's not noticeable, but when they stay with their peers it stands out” (Participant 2). According to responses, all types of schools apply the same measures to prevent discrimination among children, including private counselling and class hours. In contrast, different types of schools have different approaches to helping low-income students. In public schools, according to those interviewed, such “students receive financial assistance from the state, with additional assistance coming from charitable activities” (Participant 1). In NIS, students receive full tuition fees on admission, which also include food and clothing. In private schools, students tend to come from middle- or upper-class families, but some students may receive a merit-based scholarship if their school is able to do so.

According to experts from the NIS and public schools, the student population in these schools is heterogeneous in terms of family income. Private schools, on the other hand, tend to have students from middle- and high-income families. The majority of respondents said that the current education system is difficult for them and for the students. NIS specialists, however, described it as «effective» and that it helps students acquire “skills that would help in the selection process for the prestigious jobs that are available” (Participant 2).

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to establish the relationship between a family's social class and their children's access to education. It has been hypothesised that in modern Kazakhstan, children's access to quality education and their future academic success is influenced by the socio-economic status of their parents. The results of the study suggest that both family income and environment influence the quality of education received by children and their motivation to study. Although the questionnaire revealed no correlation between family income and academic performance, more detailed answers given by the interviewees showed that students often experience peer pressure, which impairs their academic performance. Students whose career and/or academic path is predetermined are also prone to underachievement because of their parents' willingness to either pay for their education or provide a job. While private schools differ from other types of schools in the predominance of students from high-income families, NIS schools are characterised by their students' high regard towards education.

These suggest that students’ academic path is influenced by such material means as money, which is wrong both from the moral side and from the perspective of the social system’s intended structure. The education system should be constructed in such a way that will contribute to open an individual's potential and develop it rather than utilise money as one of the main mediators.

Evaluation and Further Research

Overall, the questionnaire did not prove that the socio-economic status of parents influences their children's access to quality education and their future academic success. Regardless of familial income, the proportion of high and low-achievers was the same and students responded that they care about their education (on average) on the same level. However, from the analysis of responses on the ability of families to purchase certain household items surprisingly a high proportion of students were classified as from high-income families. Given that roughly two thirds of respondents were from rural areas it was expected that there will be a high proportion of middle and low-income students. Hence, there is a possibility that respondents’ income data turned out erroneous. Hypothetically, his variable has significant influence on both the quality of and access to education either among children or adults. Similarly, the interviewees also shared this viewpoint, stating that students have more opportunities and confidence in their studies when they are financially secure.

Despite the unanimous general answers of interviewees, some nuances personal to particular school types were also distinguishable. However, in the context of this research it was hard to collect enough data to elaborate on them. Further research should be conducted in order to investigate these variables in-depth because it has a potential to reveal the roots of the educational inequality in Kazakhstan. Once the source of the problem is found, subsequent policies, in theory, will effectively eliminate it. It is important to provide education for all regardless of the finances of an individual. The educational system should focus on ensuring inclusive, equitable and fair quality education.

References:

- Causey, J., Harnack-Eber, A., Huie, F., Lang, R., Liu, Q., Ryu, M., and Shapiro, D. (2020). COVID-19 Transfer, Mobility, and Progress, Report #1. National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. Retrieved from: https://nscresearchcenter.org/high-school-benchmarks/

- Antoninis, M., Delprato, M. & Benavot, A. (2016). Inequality in education: the challenge of measurement. In: Challenging inequalities: pathways to a just world. World social science report. Retrieved from: http://www.worldsocialscience.org/activities/world-social-science-report/2016-report-inequality/full-contents/

- Marteau, J. (2016). Post-COVID education in Kazakhstan: Heavy losses and deepening inequality. World Bank Blogs. Retrieved from: https://blogs.worldbank.org/europeandcentralasia/post-covid-education-kazakhstan-heavy-losses-and-deepening-inequality

- Rury, J.L. (1991). Review: Transformation in Perspective: Lawrence Cremin's Transformation of the School. History of Education Quarterly. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.2307/368783

- Bloom, D., Cohen, J. (2002). Education for all: an unfinished revolution. Dædalus. Retrieved from: https://www.amacad.org/publication/education-all-unfinished-revolution

- Crosnoe, R. (2011). Fitting in, standing out: Navigating the social challenges of high school to get an education. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from: https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1017/CBO9780511793264

- Jabbar, M.N., Hashmi, M.A., & Ashraf, M. (2019). Comparison between Public and Private Secondary Schools Regarding Service Quality Management and Its Effect on Students' Satisfaction in Pakistan. Retrieved from: http://pu.edu.pk/images/journal/ier/PDF-FILES/3_41_2_19.pdf

- Farooq, Sabil, M., Yuan Tong, K. (2017). A Review of Pakistan School System . Journal of Education and Practice. Retrieved from: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1133082

- Sirniö, O., Martikainen, P., & Kauppinen, T. (2016). Entering the highest and the lowest incomes: Intergenerational determinants and early-adulthood transitions. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility. Retrieved from: 10.1016/j.rssm.2016.02.004.

- Kearney, M., Levine, P. (2016). Income Inequality, Social Mobility, and the Decision to Drop Out of High School. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. Retrieved from: https://econpapers.repec.org/RePEc:bin:bpeajo:v:47:y:2016:i:2016–01:p:333–396

- Plewis, Ian & Bartley, Mel. (2013). Intra-generational social mobility and educational qualifications. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility. Retrieved from: 10.1016/j.rssm.2013.10.001.

- McKown, C., & Weinstein, R. S. (2003). The development and consequences of stereotype consciousness in middle childhood. Child Development, 74(2), 498–515. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1111/1467–8624.7402012

- Désert, M., Préaux, M., & Jund, R. (2009). So young and already victims of stereotype threat: Socio-economic status and performance of 6 to 9 years old children on Raven's progressive matrices. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 24(2), 207–218. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03173012